Adams is best known as a diplomat who shaped America's foreign policy in line with his ardently nationalist commitment to America's republican values. More recently Howe (2007) portrayed Adams as the exemplar and moral leader in an era of modernization. During Adams' lifetime, technological innovations and new means of communication spread messages of religious revival, social reform, and party politics. Goods, money, and people traveled more rapidly and efficiently than ever before. Adams was elected a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts after leaving office, serving for the last 17 years of his life with far greater acclamation than he had achieved as president. He is, so far, the only president later elected to the United States House of Representatives (though John Tyler was elected to the House of Representatives of the Confederate States just before his death in 1862). Animated by his growing revulsion against slavery, Adams became a leading opponent of the Slave Power. He predicted that if a civil war were to break out, the president could abolish slavery by using his war powers. Adams also predicted the Union's dissolution over the slavery issue, but said that if the South became independent there would be a series of bloody slave revolts.

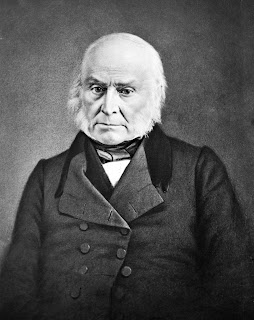

John Quincy Adams was born on July 11th, 1767 to John Adams and his wife Abigail Adams (née Smith) in a part of Braintree, Massachusetts, that is now Quincy Massachusetts. John Quincy Adams Birthplace is now part of Adams National Historical Park and open to the public. He was named for his mother's maternal grandfather, Colonel John Quincy, after whom Quincy, Massachusetts, is named. The name Quincy has subsequently been used for at least nineteen other places in the United States. Those places were either directly or indirectly named for John Quincy Adams (for example, Quincy, Illinois was named in honor of Adams while Quincy, California was named for Quincy, Illinois). The Quincy family name was pronounced kwinsi as is the name of the city in Massachusetts where Adams was born. However, all of the other place names are locally kwinsi. Though technically incorrect, this pronunciation is also commonly used for Adams' middle name. Adams first learned of the Declaration of Independence from the letters his father wrote his mother from the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. In 1779, Adams began a diary that he kept until just before he died in 1848. The massive fifty volumes are one of the most extensive collections of first-hand information from the period of the early republic and are widely cited by modern historians. Much of Adams' youth was spent accompanying his father overseas. John Adams served as an American envoy to France from 1778 until 1779 and to the Netherlands from 1780 until 1782, and the younger Adams accompanied his father on these journeys. Adams acquired an education at institutions such as Leiden University. He matriculated in Leiden January 10th 1781. For nearly three years, at the age of 14, he accompanied Francis Dana as a secretary on a mission to Saint Petersburg, Russia, to obtain recognition of the new United States. He spent time in Finland, Sweden, and Denmark and, in 1804, published a travel report of Silesia. During these years overseas, Adams became fluent in French and Dutch and became familiar with German and other European languages. He entered Harvard College and was graduated in 1787 with a Bachelor of Arts degree, Phi Beta Kappa. Adams House at Harvard College is named in honor of Adams and his father. He later earned an A.M. from Harvard in 1790. He apprenticed as an attorney with Theophilus Parsons in Newburyport, Massachusetts, from 1787 to 1789. He gained admittance to the bar in 1791 and began practicing law in Boston.

Adams first won national recognition when he published a series of widely read articles supporting Washington's decision to keep America out of the growing hostilities surrounding the French Revolution. Soon after, George Washington appointed Adams minister to the Netherlands (at the age of 26) in 1793. He did not want the position, preferring to maintain his quiet life of reading in Massachusetts, and probably would have rejected it if his father had not persuaded him to take it. On his way to the Netherlands, he was to deliver a set of documents to Chief Justice John Jay, who was negotiating the Jay Treaty. After spending some time with Jay, Adams wrote home to his father, in support of the emerging treaty because he thought America should stay out of European affairs. Historian Paul Nagel has noted that this letter reached Washington, and that parts of it were used by Washington when drafting his farewell address.

On his return to the United States, Adams was appointed a Commissioner of Monetary Affairs in Boston by a Federal District Judge, however, Thomas Jefferson rescinded this appointment. He again tried his hand as an attorney, but shortly afterward entered politics. John Quincy Adams was elected a member of the Massachusetts State Senate in April 1802. In November 1802 he ran as a Federalist for the United States House of Representatives and lost. The Massachusetts General Court elected Adams as a Federalist to the U.S. Senate soon after, and he served from March 4, 1803, until 1808, when he broke with the Federalist Party. Adams, as a Senator, had supported the Louisiana Purchase and Jefferson's Embargo Act, actions which made him very unpopular with Massachusetts Federalists. The Federalist-controlled Massachusetts Legislature chose a replacement for Adams on June 3, 1808, several months early. On June 8, Adams broke with the Federalists, resigned his Senate seat, and became a Democrat-Republican.

President James Madison appointed Adams as the first ever United States Minister to Russia in 1809 (though Francis Dana and William Short had previously been nominated to the post, neither presented his credentials at Saint Petersburg). Louisa Adams was with him in Saint Petersburg almost the entire time. While not officially a diplomat, Louisa Adams did serve an invaluable role as wife-of-diplomat, becoming a favorite of the tsar and making up for her husband's utter lack of charm. She was an indispensable part of the American mission. In 1812, Adams reported the news of Napoleon's invasion of Russia and Napoleon's disastrous retreat. In 1814, Adams was recalled from Russia to serve as chief negotiator of the U.S. commission for the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain. Finally, he was sent to be minister to the Court of St. James's (Britain) from 1815 until 1817, a post that was first held by his father.

Adams served as Secretary of State in the Cabinet of President James Monroe from 1817 until 1825. Typically, his views concurred with those espoused by Monroe. As Secretary of State, he negotiated the Adams-Onís Treaty (which acquired Florida for the United States), the Treaty of 1818, and wrote the Monroe Doctrine. Many historians regard him as one of the greatest Secretaries of State in American history.

The Floridas, still a Spanish territory but with no Spanish presence to speak of, became a refuge for runaway slaves and Indian raiders. Monroe sent in General Andrew Jackson who pushed the Seminole Indians south, executed two British merchants who were supplying weapons, deposed one governor and named another, and left an American garrison in occupation. President Monroe and all his cabinet, except Adams, believed Jackson had exceeded his instructions. Adams argued that since Spain had proved incapable of policing her territories, the United States was obliged to act in self-defense. Adams so ably justified Jackson's conduct that he silenced protests from either Spain or Britain; Congress refused to punish Jackson. Adams used the events that had unfolded in Florida to negotiate the Florida Treaty with Spain in 1819 that turned Florida over to the U.S. and resolved border issues regarding the Louisiana Purchase.

With the ongoing Oregon boundary dispute, Adams sought to negotiate a settlement with England to decide the border between the western United States and Canada. This would become the Treaty of 1818. Along with the Rush–Bagot Treaty of 1817, this marked the beginning of improved relations between the British Empire and its former colonies, and paved the way for better relations between the U.S. and Canada. The treaty had several provisions, but in particular it set the boundary between British North America and the United States along the 49th parallel through the Rocky Mountains. This settled a boundary dispute caused by ignorance of actual geography in the boundary agreed to in the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolutionary War. That earlier treaty had used the Mississippi River to determine the border, but assumed that the river extended further north than it did, and so that earlier settlement was unworkable.

By the time Monroe became president, several European powers, in particular Spain, were attempting to re-establish control over South America. On Independence Day 1821, in response to those who advocated American support for independence movements in many South American countries, Adams gave a speech in which he said that American policy was moral support for independence movements but not armed intervention. He stated that America "goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy." From this, Adams authored what came to be known as the Monroe Doctrine, which was introduced on December 2, 1823. It stated that further efforts by European countries to colonize land or interfere with states in the Americas would be viewed as acts of aggression requiring U.S. intervention. The United States, reflecting concerns raised by Great Britain, ultimately hoped to avoid having any European power take over Spain's colonies. It became a defining moment in the foreign policy of the United States and one of its longest-standing tenets, and would be invoked by many U.S. statesmen and several U.S. presidents, including Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan and others.

As the 1824 election drew near people began looking for candidates. New England voters admired Adams' patriotism and political skills and it was mainly due to their support that he entered the race. The old caucus system of the Democratic-Republican Party had collapsed; indeed the entire First Party System had collapsed and the election was a fight based on regional support. Adams had a strong base in New England. His opponents included John C. Calhoun, William H. Crawford, Henry Clay, and the hero of New Orleans, Andrew Jackson. During the campaign Calhoun dropped out, and Crawford fell ill giving further support to the other candidates. When Election Day arrived, Andrew Jackson won, although narrowly, pluralities of the popular and electoral votes, but not the necessary majority of electoral votes. Under the terms of the Twelfth Amendment, the presidential election fell to the House of Representatives, which was to choose from the top three candidates: Jackson, Adams, and Crawford. Clay had come in fourth place and thus was not on the ballot, but he retained considerable power and influence as Speaker of the House.

Clay's personal dislike for Jackson and the similarity of his American System to Adams' position on tariffs and internal improvements caused him to throw his support to Adams, who was elected by the House on February 9, 1825, on the first ballot. Adams' victory shocked Jackson, who had won the most electoral and popular votes and fully expected to be elected president. When Adams appointed Clay as Secretary of State - the position that Adams and his three predecessors had held before becoming president - Jacksonian Democrats were outraged, and claimed that Adams and Clay had struck a "corrupt bargain". This contention overshadowed Adams' term and greatly contributed to Adams' loss to Jackson four years later, in the 1828 election.

Adams served as the sixth President of the United States from March 4th, 1825, to March 4th, 1829. He took the oath of office on a book of constitutional law, instead of the more traditional Bible. Adams proposed an elaborate program of internal improvements (roads, ports and canals), a national university, and federal support for the arts and sciences. He favored a high tariff to encourage the building of factories, and restricted land sales to slow the movement west. Opposition from the states' rights faction of a hostile congress killed many of his proposals. He also reduced the national debt from $16 million to $5 million, the remainder of which was paid off by his immediate successor, Andrew Jackson. Paul Nagel argues that his political acumen was not any less developed than others were in his day, and notes that Henry Clay, one of the era's most astute politicians, was a principal advisor to Adams and supporter throughout his presidency. Nagel argues that Adams' political problems were the result of an unusually hostile Jacksonian faction, and Adams' own dislike of the office. Although a product of the political culture of his day, he refused to play politics according to the usual rules and was not as aggressive in courting political support as he could have been. He was attacked by the followers of Jackson, who accused him of being a partner to a "corrupt bargain" to obtain Clay's support in the election and then appoint him Secretary of State. Jackson defeated Adams in 1828, and created the modern Democratic party thus inaugurating the Second Party System.

During his term, Adams worked on transforming America into a world power through "internal improvements," as a part of the "American System". It consisted of a high tariff to support internal improvements such as road-building, and a national bank to encourage productive enterprise and form a national currency. In his first annual message to Congress, Adams presented an ambitious program for modernization that included roads, canals, a national university, an astronomical observatory, and other initiatives. The support for his proposals was mixed, mainly due to opposition from Jackson's followers. Some of his proposals were adopted, specifically the extension of the Cumberland Road into Ohio with surveys for its continuation west to St. Louis; the beginning of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, the construction of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal and the Louisville and Portland Canal around the falls of the Ohio; the connection of the Great Lakes to the Ohio River system in Ohio and Indiana; and the enlargement and rebuilding of the Dismal Swamp Canal in North Carolina. One of the issues which divided the administration was protective tariffs, of which Henry Clay was a leading advocate. After Adams lost control of Congress in 1827, the situation became more complicated. By signing into law the Tariff of 1828, quite unpopular in parts of the south, he further antagonized the Jacksonians.

Adams' generous policy toward Native Americans caused him trouble. Settlers on the frontier, who were constantly seeking to move westward, cried for a more expansionist policy. When the federal government tried to assert authority on behalf of the Cherokees, the governor of Georgia took up arms. Adams defended his domestic agenda as continuing Monroe's policies. In contrast, Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren instigated the policy of Indian removal to the west (i.e. the Trail of Tears.)

John Quincy Adams left office on March 4, 1829, after losing the election of 1828 to Andrew Jackson. Adams did not attend the inauguration of his successor, Andrew Jackson, who had openly snubbed him by refusing to pay the traditional "courtesy call" to the outgoing president during the weeks before his own inauguration. He was one of only three presidents who chose not to attend their respective successor's inauguration; the others were his father and Andrew Johnson.

After the inauguration of Adams in 1825, Jackson resigned from his senate seat. For four years he worked hard, with help from his supporters in Congress, to defeat Adams in the presidential election of 1828. The campaign was very much a personal one. As was the tradition of the day and age in American presidential politics, neither candidate personally campaigned, but their political followers organized many campaign events. Both candidates were rhetorically attacked in the press. This reached a low point when the press accused Jackson's wife Rachel of bigamy. She died a few weeks after the elections. Jackson said he would forgive those who insulted him, but he would never forgive the ones who had attacked his wife.

Adams lost the election by a decisive margin. He won all the same states that his father had won in the election of 1800: the New England states, New Jersey, and Delaware, as well as parts of New York and a majority of Maryland. Jackson won the rest of the states, picking up 178 electoral votes to Adams' 83 votes, and succeeded him. Adams and his father were the only U.S. presidents to serve a single term during the first 48 years of the Presidency (1789–1837). Historian Thomas Bailey observed, "Seldom has the public mind been so successfully poisoned against an honest and high-minded man.

Adams did not retire after leaving office. Instead he ran for and won a seat in the United States House of Representatives in the 1830 elections. He was the first president to serve in Congress after his term of office, and one of only two former presidents to do so (Andrew Johnson later served in the Senate). He was elected to eight terms, serving as a Representative for 17 years, from 1831 until his death.

Adams focused more on anti-slavery issues starting in 1841. He involved himself on the Amistad case which determined that the slaves that were captured in the Sierra Leone region would not be held accountable as slaves and that they could return home to their family and friends. Adams agreed for Lewis Tappan and Ellis Gray to take the stand at the Supreme Court on behalf of the African Americans after a revolt on the Spanish ship of Amistad. Adams took the case for February 24, 1841 and argued on behalf of the African Americans for four hours. His argument put an end to the Armistad affairs and freed the slaves. In authoring a change to the Tariff of 1828, he was instrumental to the compromise that ended the Nullification Crisis. When James Smithson died and left his estate to the U.S. government to build an institution of learning, congress wanted to appropriate the money for other purposes. Adams was key to ensuring that the money was instead used to build the Smithsonian Institution. He also led the fight against the gag rule, which prevented congress from hearing anti-slavery petitions. Throughout much of his congressional career, he fought it, evaded it, and tried to repeal it. In 1844 he assembled a coalition that approved his resolution to repeal the rule. He was considered by many to be the leader of the anti-slavery faction in congress, as he was one of America's most prominent opponents of slavery.

A longtime opponent of slavery, Adams used his new role in Congress to fight it. In 1836, Southern Congressmen voted in a rule, called the “gag rule,” that immediately tabled any petitions about slavery, banning discussion or debate of the slavery issue. He became a forceful opponent of this rule and conceived a way around it, attacking slavery in the House for two weeks. The gag rule prevented him from bringing slavery petitions to the floor, but he brought one anyway. It was a petition from a Georgia citizen urging disunion due to the continuation of slavery in the South. Though he certainly did not support it and made that clear at the time, his intent was to antagonize the pro-slavery faction of Congress into an open fight on the matter. The plan worked. The petition infuriated his congressional enemies, many of whom were agitating for disunion themselves. They moved for his censure over the matter, enabling Adams to openly discuss slavery during his subsequent defense. Taking advantage of his right to defend himself, Adams delivered prepared and impromptu remarks against slavery and in favor of abolition. Knowing that he would probably be acquitted, he changed the focus from his own actions to those of the slaveholders, speaking against the slave trade and the ownership of slaves. He decided that if he were censured, he would merely resign, run for the office again, and probably win easily. When his opponents realized that they played into his political strategy, they tried to bury the censure. Adams made sure this did not happen, and the debate continued. He attacked slavery and slaveholders as immoral and condemned the institution while calling for it to end. After two weeks, a vote was held, and he was not censured. He delighted in the misery he was inflicting on the slaveholders he so hated, and prided himself on being "obnoxious to the slave faction."

Although the censure of Adams over the slavery petition was ultimately abandoned, the House did address the issue of petitions from enslaved persons at a later time. Adams again argued that the right to petition was a universal right, granted by God, so that those in the weakest positions might always have recourse to those in the most powerful. Adams also called into question the actions of a House that would limit its own ability to debate and resolve questions internally. After this debate, the gag rule was ultimately retained. The discussion ignited by his actions and the attempts of others to quiet him raised questions of the right to petition, the right to legislative debate, and the morality of slavery. During the censure debate, Adams said that he took delight in the fact that southerners would forever remember him as "the acutest, the astutest, the archest enemy of southern slavery that ever existed". Later he led a committee that sought to reform Congress' rules, and he used this opportunity to try to repeal the gag rule once again. He spent two months building support for this move, but due to northern opposition, the rule narrowly survived. He fiercely criticized northern Congressmen and Senators, in particular Stephen A. Douglas, who seemed to cater to the slave faction in exchange for southern support. His opposition to slavery made him, along with Henry Clay, one of the leading opponents of Texas annexation and the Mexican–American War. He correctly predicted that both would contribute to civil war. After one of his reelection victories, he said that he must "bring about a day prophesied when slavery and war shall be banished from the face of the earth."

On February 21, 1848, the House of Representatives was discussing the matter of honoring US Army officers who served in the Mexican–American War. Adams firmly opposed this idea, so when the rest of the house erupted into 'ayes', he cried out, 'No!.' He rose to answer a question put forth by the Speaker of the House. Immediately thereafter, Adams collapsed, having suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage. Two days later, on February 23, he died with his wife and son at his side in the Speaker's Room inside the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. His last words were "This is the last of earth. I am content." He died at 7:20 P.M. His original interment was temporary, in the public vault at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Later, he was interred in the family burial ground in Quincy across from the First Parish Church, called Hancock Cemetery. After Louisa's death in 1852, his son, Charles Francis Adams, had his parents reinterred in the expanded family crypt in the United First Parish Church across the street, next to John and Abigail. Both tombs are viewable by the public. Adams' original tomb at Hancock Cemetery is still there and marked simply "J.Q. Adams".

John Quincy Adams and Louisa Catherine Adams had three sons and a daughter. Their daughter, Louisa, was born in 1811 but died in 1812 while the family was in Russia. They named their first son George Washington Adams (1801-1829) after the first president. Both George and their second son, John (1803 - 1834), led troubled lives and died in early adulthood. (George committed suicide and John was expelled from Harvard before his 1823 graduation.)

Adams' youngest son, Charles Francis Adams (who named his own son John Quincy), also pursued a career in diplomacy and politics. In 1870 Charles Francis built the first memorial presidential library in the United States, to honor his father. The Stone Library includes over 14,000 books written in twelve languages. The library is located in the "Old House" at Adams National Historical Park in Quincy, Massachusetts.

John Adams and John Quincy Adams were the first father and son to each serve as president (the others being George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush). Each Adams served only one term as president.

Source: Wikipedia

This work is released under

CC 3.0 BY-SA - Creative Commons

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.