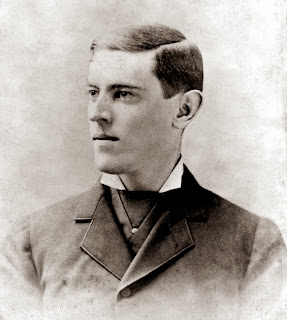

Wilson was born in Staunton, Virginia, on December 28, 1856. His birthplace in Staunton, at 18–24 North Coalter Street, is now the location of the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library. He was the third of four children of Joseph Ruggles Wilson (1822–1903) and Jessie Janet Woodrow (1826–1888). His ancestry was Scottish and Scots-Irish. His paternal grandparents immigrated to the United States from Strabane, County Tyrone, Ireland (now Northern Ireland), in 1807. His mother was born in Carlisle, Cumberland, England, the daughter of Rev. Dr. Thomas Woodrow, born in Paisley, Scotland, and Marion Williamson from Glasgow. His grandparents' whitewashed house has become a tourist attraction in Northern Ireland.

Wilson was born in Staunton, Virginia, on December 28, 1856. His birthplace in Staunton, at 18–24 North Coalter Street, is now the location of the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library. He was the third of four children of Joseph Ruggles Wilson (1822–1903) and Jessie Janet Woodrow (1826–1888). His ancestry was Scottish and Scots-Irish. His paternal grandparents immigrated to the United States from Strabane, County Tyrone, Ireland (now Northern Ireland), in 1807. His mother was born in Carlisle, Cumberland, England, the daughter of Rev. Dr. Thomas Woodrow, born in Paisley, Scotland, and Marion Williamson from Glasgow. His grandparents' whitewashed house has become a tourist attraction in Northern Ireland. Wilson's father was originally from Steubenville, Ohio, where his grandfather published a newspaper, The Western Herald and Gazette, which was pro-tariff and anti-slavery. Wilson's parents moved south in 1851 and identified with the Confederacy. His father defended slavery, owned slaves and set up a Sunday school for them. They cared for wounded soldiers at their church. The father also briefly served as a chaplain to the Confederate Army. Woodrow Wilson's earliest memory, from the age of three, was of hearing that Abraham Lincoln had been elected and that a war was coming. Wilson would forever recall standing for a moment at Robert E. Lee's side and looking up into his face.

Wilson was over ten years of age before he learned to read. His difficulty reading may have indicated dyslexia, but as a teenager he taught himself shorthand to compensate. He was able to achieve academically through determination and self-discipline. He studied at home under his father's guidance and took classes in a small school in Augusta. During Reconstruction, Wilson lived in Columbia, South Carolina, the state capital, from 1870 to 1874, where his father was professor at the Columbia Theological Seminary.

Wilson attended Davidson College in North Carolina for the 1873–1874 school year. After medical ailments kept him from returning for a second year, he transferred to Princeton as a freshman when his father took a teaching position at the university. Graduating in 1879, Wilson became a member of Phi Kappa Psi fraternity. Beginning in his second year, he read widely in political philosophy and history. Wilson credited the British parliamentary sketch-writer Henry Lucy as his inspiration to enter public life. He was active in the undergraduate American Whig-Cliosophic Society literary and debating society, serving as speaker of the Whig Party and writing for the Nassau Literary Review, organized a separate Liberal Debating Society, and later coached the Whig-Clio Debate Panel.

In 1879, Wilson attended law school at the University of Virginia for one year. Although he never graduated, during his time at the university he was heavily involved in the Virginia Glee Club and the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society, serving as the society's president. His frail health dictated withdrawal, and he went home to Wilmington, North Carolina, where he continued his studies.

In January 1882, Wilson started a law practice in Atlanta. One of his University of Virginia classmates, Edward Ireland Renick, invited him to join his new law practice as partner and Wilson joined him in May 1882. He passed the Georgia Bar. On October 19, 1882, he appeared in court before Judge George Hillyer to take his examination for the bar, which he passed easily. Competition was fierce in a city with 143 other lawyers, and he found few cases to keep him occupied.

Nevertheless, he found staying current with the law obstructed his plans to study government to achieve his long-term plans for a political career. In April 1883, Wilson applied to the Johns Hopkins University to study for a doctorate in history and political science and began his studies there in the fall.

Wilson's mother was possibly a hypochondriac and Wilson himself seemed to think that he was often in poorer health than he really was. He suffered from hypertension at a relatively early age and may have suffered his first stroke when he was 39.

Wilson's mother was possibly a hypochondriac and Wilson himself seemed to think that he was often in poorer health than he really was. He suffered from hypertension at a relatively early age and may have suffered his first stroke when he was 39.In 1885, he married Ellen Louise Axson, the daughter of a minister from Savannah, Georgia, during a visit to her relatives in Rome, Georgia. They had three daughters: Margaret Woodrow Wilson (1886–1944); Jessie Wilson (1887–1933); and Eleanor R. Wilson (1889–1967). Ellen Axson Wilson died in 1914, and in 1915 Wilson married Edith Galt, a direct descendant of the Native American woman Pocahontas. Wilson is one of only three presidents to be widowed while in office.

Wilson was an early automobile enthusiast, and he took daily rides while he was President. His favorite car was a 1919 Pierce-Arrow, in which he preferred to ride with the top down. His enjoyment of motoring made him an advocate of funding for public highways.

Wilson was an avid baseball fan. In 1915, he became the first sitting president to attend a World Series game. Wilson had been a center fielder during his Davidson College days. When he transferred to Princeton, he was unable to make the varsity team and so became the team's assistant manager. He was the first President to throw out a first ball at a World Series game.

He cycled regularly, including several cycling vacations in the English Lake District. Unable to cycle around Washington, D.C., as President, Wilson took to playing golf, although he played with more enthusiasm than skill. Wilson holds the record of all the presidents for the most rounds of golf, over 1,000, or almost one every other day. During the winter, the Secret Service would paint golf balls with black paint so Wilson could hit them around in the snow on the White House lawn.

In 1910, Wilson ran for Governor of New Jersey against the Republican candidate Vivian M. Lewis, the State Commissioner of Banking and Insurance. Wilson's campaign focused on his independence from machine politics, and he promised that if elected he would not be beholden to party bosses. Wilson soundly defeated Lewis in the general election by a margin of more than 49,000 votes, although Republican William Howard Taft had carried New Jersey in the 1908 presidential election by more than 80,000 votes. Historian and Teddy Roosevelt biographer Edmund Morris called Wilson in the Governor's race a "dark horse" and attributed his and others' success against the Taft Republicans in 1910 in part to the emergent national progressive message enunciated by Roosevelt in his post-presidency.

In the 1910 election, the Democrats also took control of the General Assembly. The State Senate, however, remained in Republican control by a slim margin. After taking office, Wilson set in place his reformist agenda, ignoring the demands of party machinery. While governor, in a period spanning six months, Wilson established state primaries. This all but took the party bosses out of the presidential election process in the state. He also revamped the public utility commission and introduced worker's compensation.

Wilson's popularity as governor and his status in the national media

gave impetus to his presidential campaign in 1912. He chose Indiana

Governor Thomas R. Marshall as his running mate and selected William Frank McCombs,

a New York lawyer and a friend from college days, to manage his

campaign. Much of Wilson's support came from the South, especially from

young progressives in that region, especially intellectuals, editors and

lawyers. Wilson managed to maneuver through the complexities of local

politics. For example, in Tennessee the Democratic Party was divided on

the issue of prohibition. Wilson was progressive and sober, but not a

dry, and appealed to both sides. They united behind him to win the

presidential election in the state, but divided over state politics and

lost the gubernatorial election.

Wilson's popularity as governor and his status in the national media

gave impetus to his presidential campaign in 1912. He chose Indiana

Governor Thomas R. Marshall as his running mate and selected William Frank McCombs,

a New York lawyer and a friend from college days, to manage his

campaign. Much of Wilson's support came from the South, especially from

young progressives in that region, especially intellectuals, editors and

lawyers. Wilson managed to maneuver through the complexities of local

politics. For example, in Tennessee the Democratic Party was divided on

the issue of prohibition. Wilson was progressive and sober, but not a

dry, and appealed to both sides. They united behind him to win the

presidential election in the state, but divided over state politics and

lost the gubernatorial election.The convention deadlocked for more than 40 ballots as no candidate could reach the two-thirds vote required to win the nomination. A leading contender was House Speaker Champ Clark, a prominent progressive strongest in the border states. Other contenders were Governor Judson Harmon of Ohio, and Representative Oscar Underwood of Alabama. They lacked Wilson's charisma and dynamism. Publisher William Randolph Hearst, a leader of the left wing of the party, supported Clark. William Jennings Bryan, the nominee in 1896, 1900 and 1908, played a critical role in opposition to any candidate who had the support of "the financiers of Wall Street". He finally announced for Wilson, who won on the 46th ballot.

In the campaign Wilson promoted the "New Freedom", emphasizing limited federal government and opposition to monopoly powers, often after consultation with his chief advisor Louis D. Brandeis. In the contest for the Republican nomination, President William Howard Taft defeated former president Theodore Roosevelt, who then ran as a Bull Moose Party candidate, which assisted in Wilson's success in the electoral college. Wilson took 41.8% of the popular vote and won 435 electoral votes from 40 states. It is not clear if Roosevelt cost fellow Republican Taft, or fellow progressive Wilson more support.

Wilson was the first Southerner in the White House since 1869 and worked closely with Southern leaders. Since 1856, he and Grover Cleveland were the only Democrats elected president, so he felt a need to appoint Democrats to all federal positions.

In resolving economic policy issues, he had to manage the conflict

between two wings of his party: the agrarian wing led by Bryan and the

pro-business wing. With large Democratic majorities in Congress and a

healthy economy, he promptly seized the opportunity to implement his

agenda. Wilson experienced early success by implementing his "New Freedom" pledges of antitrust modification, tariff revision, and reform in banking and currency matters.

He held the first modern presidential press conference, on March 15,

1913, in which reporters were allowed to ask him questions. In 1913, he also became the first president to deliver the State of the Union address in person since 1801 when Thomas Jefferson discontinued this practice.

In resolving economic policy issues, he had to manage the conflict

between two wings of his party: the agrarian wing led by Bryan and the

pro-business wing. With large Democratic majorities in Congress and a

healthy economy, he promptly seized the opportunity to implement his

agenda. Wilson experienced early success by implementing his "New Freedom" pledges of antitrust modification, tariff revision, and reform in banking and currency matters.

He held the first modern presidential press conference, on March 15,

1913, in which reporters were allowed to ask him questions. In 1913, he also became the first president to deliver the State of the Union address in person since 1801 when Thomas Jefferson discontinued this practice.Wilson's first wife Ellen died on August 6, 1914, casting him into a deep depression. In 1915, he met Edith Galt. They married later that year on December 18.

Wilson secured passage of the Federal Reserve Act in late 1913. He had tried to find a middle ground between conservative Republicans, led by Senator Nelson W. Aldrich, and the powerful left wing of the Democratic party, led by William Jennings Bryan, who strenuously denounced private banks and Wall Street. The latter group wanted a government-owned central bank that could print paper money as Congress required. The compromise, based on the Aldrich Plan but sponsored by Democratic Congressmen Carter Glass and Robert Owen, allowed the private banks to control the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks, but appeased the agrarians by placing controlling interest in the System in a central board appointed by the president with Senate approval. Moreover, Wilson convinced Bryan's supporters that because Federal Reserve notes were obligations of the government, the plan met their demands for an elastic currency. Having 12 regional banks was meant to weaken the influence of the powerful New York banks, a key demand of Bryan's allies in the South and West. This decentralization was a key factor in winning Glass' support. The final plan passed in December 1913. Some bankers felt it gave too much control to Washington, and some reformers felt it allowed bankers to maintain too much power. Several Congressmen claimed that New York bankers feigned their disapproval.

Wilson named Paul Warburg and other prominent bankers to direct the new system. While power was supposed to be decentralized, the New York branch dominated the Fed as the "first among equals". The new system began operations in 1915 and played a major role in financing the Allied and American war effort. The strengthening of the Federal Reserve was later a major accomplishment of the New Deal.

Wilson broke with the big lawsuit tradition of his predecessors Taft and Roosevelt as Trustbusters, finding a new approach to encouraging competition through the Federal Trade Commission, which stopped perceived unfair trade practices. In addition, he pushed through Congress the Clayton Antitrust Act making certain business practices illegal (such as price discrimination,

agreements prohibiting retailers from handling other companies'

products, and directorates and agreements to control other companies).

The power of this legislation was greater than that of previous anti-trust

laws because individual officers of corporations could be held

responsible if their companies violated the laws. More importantly, the

new laws set out clear guidelines that corporations could follow, a

dramatic improvement over the previous uncertainties. This law was

considered the "Magna Carta" of labor by Samuel Gompers

because it ended union liability antitrust laws. In 1916, under threat

of a national railroad strike, Wilson approved legislation that

increased wages and cut working hours of railroad employees; there was

no strike.

Wilson broke with the big lawsuit tradition of his predecessors Taft and Roosevelt as Trustbusters, finding a new approach to encouraging competition through the Federal Trade Commission, which stopped perceived unfair trade practices. In addition, he pushed through Congress the Clayton Antitrust Act making certain business practices illegal (such as price discrimination,

agreements prohibiting retailers from handling other companies'

products, and directorates and agreements to control other companies).

The power of this legislation was greater than that of previous anti-trust

laws because individual officers of corporations could be held

responsible if their companies violated the laws. More importantly, the

new laws set out clear guidelines that corporations could follow, a

dramatic improvement over the previous uncertainties. This law was

considered the "Magna Carta" of labor by Samuel Gompers

because it ended union liability antitrust laws. In 1916, under threat

of a national railroad strike, Wilson approved legislation that

increased wages and cut working hours of railroad employees; there was

no strike. Wilson spent 1914 through to the beginning of 1917 trying to keep America out of the war in Europe. He offered to be a mediator, but neither the Allies nor the Central Powers took his requests seriously. Republicans, led by Theodore Roosevelt, strongly criticized Wilson's refusal to build up the U.S. Army in anticipation of the threat of war. Wilson won the support of the peace element (especially women and churches) by arguing that an army buildup would provoke war. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, whose pacifist recommendations were ignored by Wilson, resigned in 1915.

On December 18, 1916, Wilson unsuccessfully offered to mediate peace. As a preliminary, he asked both sides to state their minimum terms necessary for future security. The Central Powers replied that victory was certain, and the Allies required the dismemberment of their enemies' empires. No desire for peace or common ground existed, and the offer lapsed.

While German submarines were killing sailors and civilian passengers, Wilson demanded that Germany stop, but he kept the U.S. out of the war. Britain had declared a blockade of Germany to prevent neutral ships from carrying contraband goods to Germany. Wilson protested some British violation of neutral rights, where no one was killed. His protests were mild, and the British knew America would not see it as a casus belli.

During the 1916 election campaign, while drafting the platform on which

he and the Democratic Party would run, Wilson received a suggestion that

helped give the document a sharper political focus. Senator Owen of

Oklahoma urged Wilson to take ideas from the Progressive Party platform

of 1912 “as a means of attaching to our party progressive Republicans

who are in sympathy with us in so large a degree.” Wilson liked this

suggestion and asked Owen to specify the 1912 Progressive ideas to

include. In response, Owen highlighted federal legislation to promote

workers’ health and safety, prohibit child labour, provide unemployment

compensation, require an eight-hour day and six-day workweek, and

establish minimum wages and maximum hours. Wilson, in turn, included in

his draft platform a plank that called for all work performed by and for

the federal government to provide a minimum wage, an eight-hour day and

six-day workweek, health and safety measures, the prohibition of child

labour, and (his own additions) safeguards for female workers and a

retirement program.

During the 1916 election campaign, while drafting the platform on which

he and the Democratic Party would run, Wilson received a suggestion that

helped give the document a sharper political focus. Senator Owen of

Oklahoma urged Wilson to take ideas from the Progressive Party platform

of 1912 “as a means of attaching to our party progressive Republicans

who are in sympathy with us in so large a degree.” Wilson liked this

suggestion and asked Owen to specify the 1912 Progressive ideas to

include. In response, Owen highlighted federal legislation to promote

workers’ health and safety, prohibit child labour, provide unemployment

compensation, require an eight-hour day and six-day workweek, and

establish minimum wages and maximum hours. Wilson, in turn, included in

his draft platform a plank that called for all work performed by and for

the federal government to provide a minimum wage, an eight-hour day and

six-day workweek, health and safety measures, the prohibition of child

labour, and (his own additions) safeguards for female workers and a

retirement program. Wilson narrowly won the election, defeating Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes. As governor of New York from 1907 to 1910, Hughes had a progressive record strikingly similar to Wilson's as governor of New Jersey. Theodore Roosevelt would comment that the only thing different between Hughes and Wilson was a shave. However, Hughes had to try to hold together a coalition of conservative Taft supporters and progressive Roosevelt partisans and so his campaign never seemed to take a definite form. Wilson ran on his record and ignored Hughes, reserving his attacks for Roosevelt. When asked why he did not attack Hughes directly, Wilson told a friend to "Never murder a man who is committing suicide."

The result was exceptionally close and the outcome was in doubt for several days. The vote came down to several close states. Wilson won California by 3,773 votes out of almost a million votes cast and New Hampshire by 54 votes. Hughes won Minnesota by 393 votes out of over 358,000. In the final count, Wilson had 277 electoral votes vs. Hughes's 254. Wilson was able to win by picking up many votes that had gone to Teddy Roosevelt or Eugene V. Debs in 1912.

The U.S. had made a declaration of neutrality in 1914. Wilson warned citizens not to take sides in the war for fear of endangering wider U.S. policy. In his address to Congress in 1914, Wilson stated, "Such divisions amongst us would be fatal to our peace of mind and might seriously stand in the way of the proper performance of our duty as the one great nation at peace, the one people holding itself ready to play a part of impartial mediation and speak the counsels of peace and accommodation, not as a partisan, but as a friend."

The U.S. maintained neutrality despite increasing pressure placed on Wilson after the sinking of the British passenger liner RMS Lusitania with arms and American citizens on board. Wilson found it increasingly difficult to maintain U.S. neutrality after Germany, despite its promises in the Arabic pledge and the Sussex pledge, initiated a program of unrestricted submarine warfare early in 1917 that threatened U.S. commercial shipping. Following the revelation of the Zimmermann Telegram, Germany's attempt to enlist Mexico as an ally against the U.S., Wilson took America into World War I to make "the world safe for democracy." The U.S. did not sign a formal alliance with the United Kingdom or France but operated as an "associated" power. The U.S. raised a massive army through conscription and Wilson gave command to General John J. Pershing, allowing Pershing a free hand as to tactics, strategy and even diplomacy.

Wilson had decided by then that the war had become a real threat to humanity. Unless the U.S. threw its weight into the war, as he stated in his declaration of war speech on April 2, 1917, western civilization itself could be destroyed. His statement announcing a "war to end war" meant that he wanted to build a basis for peace that would prevent future catastrophic wars and needless death and destruction. This provided the basis of Wilson's Fourteen Points, which were intended to resolve territorial disputes, ensure free trade and commerce, and establish a peacemaking organization. Included in these fourteen points was the proposal for the League of Nations.

Woodrow Wilson delivered his War Message to Congress on the

evening of April 2, 1917. Introduced to great applause, he remained

intense and almost motionless for the entire speech, only raising one

arm as his only bodily movement.

Woodrow Wilson delivered his War Message to Congress on the

evening of April 2, 1917. Introduced to great applause, he remained

intense and almost motionless for the entire speech, only raising one

arm as his only bodily movement.Wilson announced that his previous position of "armed neutrality" was no longer tenable now that the Imperial German Government had announced that it would use its submarines to sink any vessel approaching the ports of Great Britain, Ireland or any of the Western Coasts of Europe. He advised Congress to declare that the recent course of action taken by the Imperial German Government constituted an act of war. He proposed that the United States enter the war to "vindicate principles of peace and justice in the life of the world as against selfish and autocratic power". He also charged that Germany had "filled our unsuspecting communities and even our offices of government with spies and set criminal intrigues everywhere afoot against our national unity of counsel, our peace within and without our industries and our commerce". Furthermore, the United States had intercepted a telegram sent to the German ambassador in Mexico City that evidenced Germany's attempt to instigate a Mexican attack upon the U.S. The German government, Wilson said, "means to stir up enemies against us at our very doors".

He then warned that "if there should be disloyalty, it will be dealt with a firm hand of repression." Wilson closed with the statement that the world must be again safe for democracy.

With 50 Representatives and 6 Senators in opposition, the declaration of war by the United States against Germany was passed by the Congress on April 4, 1917, and was approved by the President on April 6, 1917.

In a speech to Congress on January 8, 1918, Wilson articulated America's war aims. It was the clearest expression of intention made by any of the belligerent nations. The speech, authored principally by Walter Lippmann, expressed Wilson's progressive domestic policies into comparably idealistic equivalents for the international arena: self-determination, open agreements, international cooperation. Promptly dubbed the Fourteen Points, Wilson attempted to make them the basis for the treaty that would mark the end of the war. They ranged from the most generic principles like the prohibition of secret treaties to such detailed outcomes as the creation of an independent Poland with access to the sea.

After World War I, Wilson participated in negotiations with the

stated aim of assuring statehood for formerly oppressed nations and an

equitable peace. On January 8, 1918, Wilson made his famous Fourteen Points address, introducing the idea of a League of Nations,

an organization with a stated goal of helping to preserve territorial

integrity and political independence among large and small nations

alike.

After World War I, Wilson participated in negotiations with the

stated aim of assuring statehood for formerly oppressed nations and an

equitable peace. On January 8, 1918, Wilson made his famous Fourteen Points address, introducing the idea of a League of Nations,

an organization with a stated goal of helping to preserve territorial

integrity and political independence among large and small nations

alike.Wilson intended the Fourteen Points as a means toward ending the war and achieving an equitable peace for all the nations. He spent six months in Paris for the Peace Conference (making him the first U.S. president to travel to Europe while in office). He was not well-regarded at the Conference. As John Maynard Keynes observed: "He not only had no proposals in detail, but he was in many respects, perhaps inevitably, ill-informed as to European conditions. And not only was he ill-informed - that was true of Mr. Lloyd George also - but his mind was slow and unadaptable...There can seldom have been a statesman of the first rank more incompetent than the President in the agilities of the council chamber." He worked tirelessly to promote his plan. The charter of the proposed League of Nations was incorporated into the conference's Treaty of Versailles. Japan proposed that the Covenant include a racial equality clause. Wilson was indifferent to the issue, but acceded to strong opposition from Australia and Britain. After the conference, Wilson said that "at last the world knows America as the savior of the world!"

Wilson's administration did not plan for the process of demobilization at the war's end. Though some advisers tried to engage the President's attention to what they called "reconstruction", his tepid support for a federal commission evaporated with the election of 1918. Republican gains in the Senate meant that his opposition would have to consent to the appointment of commission members. Instead, Wilson favored the prompt dismantling of wartime boards and regulatory agencies.

Demobilization proved chaotic and violent. Four million soldiers were sent home with little planning, little money, and few benefits. A wartime bubble in prices of farmland burst, leaving many farmers bankrupt or deeply in debt after they purchased new land. Major strikes in the steel, coal, and meatpacking industries followed in 1919. Serious race riots hit Chicago, Omaha, and two dozen other cities.

In 1921, Wilson and his wife Edith retired from the White House to an elegant 1915 town house in the Embassy Row (Kalorama) section of Washington, D.C. Wilson continued going for daily drives, and attended Keith's vaudeville theatre on Saturday nights. Wilson was one of only two Presidents (Theodore Roosevelt was the first) to have served as president of the American Historical Association.

In 1921, Wilson and his wife Edith retired from the White House to an elegant 1915 town house in the Embassy Row (Kalorama) section of Washington, D.C. Wilson continued going for daily drives, and attended Keith's vaudeville theatre on Saturday nights. Wilson was one of only two Presidents (Theodore Roosevelt was the first) to have served as president of the American Historical Association.Wilson attended only two state occasions in his retirement: the ceremonies preceding the burial of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery, in Arlington, Virginia, on Armistice Day (November 11), 1921; and President Warren G. Harding's state funeral in the U.S. Capitol on August 8, 1923. On November 10, 1923, Wilson made a short Armistice Day radio speech from the library of his home, his last national address. The following day, Armistice Day itself, he spoke briefly from the front steps to more than 20,000 well wishers gathered outside the house.

On February 3, 1924, Wilson died in his S Street home as a result of a stroke and other heart-related problems. He was buried in Washington National Cathedral, the only president buried in Washington, D.C.

Mrs. Wilson stayed in the home another 37 years, dying there on December 28, 1961, the day she was to be the guest of honor at the opening of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge across the Potomac River near and in Washington, D.C.

Mrs. Wilson left the home and much of the contents to the National Trust for Historic Preservation to be made into a museum honoring her husband. The Woodrow Wilson House opened to the public in 1963, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964, and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

Wilson wrote his one-page will on May 31, 1917, and appointed his wife Edith as his executrix. He left his daughter Margaret an annuity of $2,500 annually for as long as she remained unmarried, and left to his daughters what had been his first wife's personal property. The rest he left to Edith as a life estate with the provision that at her death, his daughters would divide the estate among themselves. In the event that Edith had a child, her children would inherit on an equal footing with his daughters. As the second Mrs. Wilson had no children from either of her marriages, he was thus providing for the child of a possible subsequent third marriage on her part.

Sources: Wikipedia

This work released through CC 3.0 BY-SA - Creative Commons

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.