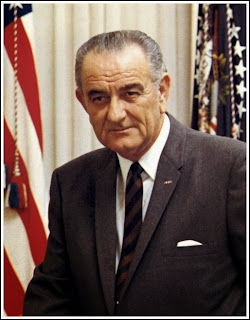

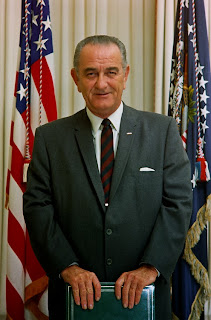

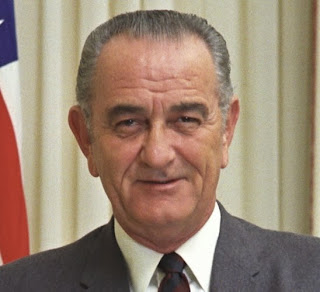

Lyndon Baines Johnson (August 27, 1908 – January 22, 1973), often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States (1963–1969), a position he assumed after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States (1961–1963). He is one of only four people who served in all four elected federal offices of the United States: Representative, Senator, Vice President, and President. Johnson, a Democrat from Texas, served as a United States Representative from 1937 to 1949 and as a Senator from 1949 to 1961, including six years as United States Senate Majority Leader, two as Senate Minority Leader and two as Senate Majority Whip. After campaigning unsuccessfully for the Democratic nomination in 1960, Johnson was asked by John F. Kennedy to be his running mate for the 1960 presidential election. Johnson succeeded to the presidency following the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, completed Kennedy's term and was elected President in his own right, winning by a large margin over Barry Goldwater in the 1964 election.

Lyndon Baines Johnson (August 27, 1908 – January 22, 1973), often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States (1963–1969), a position he assumed after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States (1961–1963). He is one of only four people who served in all four elected federal offices of the United States: Representative, Senator, Vice President, and President. Johnson, a Democrat from Texas, served as a United States Representative from 1937 to 1949 and as a Senator from 1949 to 1961, including six years as United States Senate Majority Leader, two as Senate Minority Leader and two as Senate Majority Whip. After campaigning unsuccessfully for the Democratic nomination in 1960, Johnson was asked by John F. Kennedy to be his running mate for the 1960 presidential election. Johnson succeeded to the presidency following the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, completed Kennedy's term and was elected President in his own right, winning by a large margin over Barry Goldwater in the 1964 election.Johnson was greatly supported by the Democratic Party and as President, he was responsible for designing the "Great Society" legislation that included laws that upheld civil rights, public broadcasting, Medicare, Medicaid, environmental protection, aid to education, aid to the arts, urban and rural development, and his "War on Poverty." Assisted in part by a growing economy, the War on Poverty helped millions of Americans rise above the poverty line during Johnson's presidency. Civil rights bills signed by Johnson banned racial discrimination in public facilities, interstate commerce, the workplace, and housing, and a powerful voting rights act guaranteed full voting rights for citizens of all races. With the passage of the sweeping Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, the country's immigration system was reformed and all national origins quotas were removed. Johnson was renowned for his domineering personality and the "Johnson treatment," his coercion of powerful politicians in order to advance legislation.

Meanwhile, Johnson escalated American involvement in the Vietnam War. In 1964, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which essentially gave Johnson the power to use any degree of military force in Southeast Asia without having to ask for an official declaration of war. The number of American military personnel in Vietnam increased dramatically, from 16,000 advisors/soldiers in 1963 to 550,000 combat troops in early 1968, as American casualties soared and the peace process bogged down. Massive bombing campaigns targeting North Vietnamese cities were ordered, and millions of gallons of the herbicide Agent Orange were sprayed on Vietnamese land. Despite the growing number of American troops and the sustained bombing, the war showed no signs of ending and the public began to doubt the administration's optimistic claims that victory was close at hand. Growing unease with the war stimulated a large, angry antiwar movement based especially on university campuses in the U.S. and abroad. Johnson faced further troubles when summer riots broke out in most major cities after 1965, and crime rates soared, as his opponents raised demands for "law and order" policies.

While he began his presidency with widespread approval, support for Johnson declined as the public became further upset with both the war and the growing violence at home. The Democratic Party split in multiple feuding factions, and after Johnson did poorly in the 1968 New Hampshire primary, he ended his bid for reelection. Republican Richard Nixon was elected to succeed him, and Johnson died four years after he left office. Historians argue that Johnson's presidency marked the peak of modern liberalism in the United States after the New Deal era. Johnson is ranked favorably by some historians because of his domestic policies.

While he began his presidency with widespread approval, support for Johnson declined as the public became further upset with both the war and the growing violence at home. The Democratic Party split in multiple feuding factions, and after Johnson did poorly in the 1968 New Hampshire primary, he ended his bid for reelection. Republican Richard Nixon was elected to succeed him, and Johnson died four years after he left office. Historians argue that Johnson's presidency marked the peak of modern liberalism in the United States after the New Deal era. Johnson is ranked favorably by some historians because of his domestic policies.Lyndon Baines Johnson was born in Stonewall, Texas, in a small farmhouse on the Pedernales River, the oldest of five children. His parents, Samuel Ealy Johnson, Jr., and Rebekah Baines, had three girls and two boys: Johnson and his brother, Sam Houston Johnson (1914–78), and sisters Rebekah (1910–78), Josefa (1912–61), and Lucia (1916–97). The nearby small town of Johnson City, Texas, was named after LBJ's father's cousin, James Polk Johnson, whose forebears had moved west from Oglethorpe County, Georgia. Johnson had English, Ulster Scot, and German ancestry. In school, Johnson was an awkward, talkative youth and was elected president of his 11th-grade class. He graduated from Johnson City High School (1924), having participated in public speaking, debate, and baseball.

Johnson was maternally descended from a pioneer Baptist clergyman, George Washington Baines, who pastored eight churches in Texas, as well as others in Arkansas and Louisiana. Baines was also the president of Baylor University during the American Civil War. George Baines was the grandfather of Johnson's mother, Rebekah Baines Johnson (1881–1958).

Johnson's grandfather, Samuel Ealy Johnson, Sr., was raised as a Baptist. Subsequently, in his early adulthood, he became a member of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). In his later years the grandfather became a Christadelphian; Johnson's father also joined the Christadelphian Church toward the end of his life. Later, as a politician, Johnson was influenced in his positive attitude toward Jews by the religious beliefs that his family, especially his grandfather, had shared with him.

In 1926, Johnson enrolled in Southwest Texas State Teachers' College (now Texas State University). He worked his way through school, participated in debate and campus politics, and edited the school newspaper called The College Star, now known as The University Star. The college years refined his skills of persuasion and political organization. For nine months, from 1928 to 1929, Johnson paused his studies to teach Mexican-American children at the segregated Welhausen School in Cotulla, some 90 miles south of San Antonio in La Salle County. The job helped him save money to complete his education, and he graduated in 1930. He then taught in Pearsall High School in Pearsall, Texas, and afterwards took a position as teacher of public speaking at Sam Houston High School in Houston.

Johnson married Claudia Alta Taylor (nicknamed "Lady Bird") of Karnack, Texas on November 17, 1934, after he attended Georgetown University Law Center for several months. They had two daughters, Lynda Bird, born in 1944, and Luci Baines, born in 1947. Johnson had a practice of giving people and animals names with his and his wife's initials, as he did with his daughters and with his dog, Little Beagle Johnson.

In 1935, he was appointed head of the Texas National Youth Administration, which enabled him to use the government to create education and job opportunities for young people. He resigned two years later to run for Congress. Johnson, a notoriously tough boss throughout his career, often demanded long workdays and work on weekends.

In 1937, Johnson successfully contested a special election for Texas's 10th congressional district, that covered Austin and the surrounding hill country. He ran on a New Deal platform and was effectively aided by his wife. He served in the House from April 10, 1937, to January 3, 1949.

In 1937, Johnson successfully contested a special election for Texas's 10th congressional district, that covered Austin and the surrounding hill country. He ran on a New Deal platform and was effectively aided by his wife. He served in the House from April 10, 1937, to January 3, 1949.In the 1948 elections, Johnson again ran for the Senate and won. This election was highly controversial: in a three-way Democratic Party primary Johnson faced a well-known former governor, Coke Stevenson, and a third candidate. Johnson drew crowds to fairgrounds with his rented helicopter dubbed "The Johnson City Windmill". He raised money to flood the state with campaign circulars and won over conservatives by voting for the Taft-Hartley act (curbing union power) as well as by criticizing unions.

Stevenson came in first but lacked a majority, so a runoff was held. Johnson campaigned even harder this time around, while Stevenson's efforts were surprisingly poor. The runoff count took a week. The Democratic State Central Committee (not the State of Texas, because the matter was a party primary) handled the count, and it finally announced that Johnson had won by 87 votes. By a majority of one member (29–28) the committee voted to certify Johnson's nomination, with the last vote cast on Johnson's behalf by Temple, Texas, publisher Frank W. Mayborn, who rushed back to Texas from a business trip in Nashville, Tennessee. There were many allegations of fraud on both sides. Thus one writer alleges that Johnson's campaign manager, future Texas governor John B. Connally, was connected with 202 ballots in Precinct 13 in Jim Wells County that had curiously been cast in alphabetical order and just at the close of polling. Some of these voters swore that they had not voted that day. Robert Caro argued in his 1989 book that Johnson had stolen the election in Jim Wells County and other counties in South Texas, as well as rigging 10,000 ballots in Bexar County alone. An election judge, Luis Salas, said in 1977, that he had certified 202 fraudulent ballots for Johnson.

The state Democratic convention upheld Johnson. Stevenson went to court, but - with timely help from his friend Abe Fortas - Johnson prevailed. Johnson was elected senator in November and went to Washington tagged with the ironic label "Landslide Lyndon," which he often used deprecatingly to refer to himself.

Johnson's success in the Senate made him a possible Democratic presidential candidate. He had been the "favorite son" candidate of the Texas delegation at the Party's national convention in 1956, and appeared to be in a strong position to run for the 1960 Presidential nomination. However, Johnson's late entry into that campaign, coupled with a reluctance to leave Washington, allowed the rival Kennedy campaign to secure a substantial lead among Democratic state party officials. Caro argues that Johnson's apparent ambivalence towards entering the race was caused by an overwhelming fear of failure.

Johnson also sought a third term in the U.S. Senate. According to Robert Caro, "On November 8, 1960, Lyndon Johnson won election for both the vice presidency of the United States, on the Kennedy-Johnson ticket, and for a third term as Senator (he had Texas law changed to allow him to run for both offices). When he won the vice presidency, he made arrangements to resign from the Senate, as he was required to do under federal law, as soon as it convened on January 3, 1961." (In 1988, Lloyd Bentsen, the Vice Presidential running mate of Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis, and also a Senator from Texas, took advantage of "Lyndon's law," and was able to retain his seat in the Senate despite Dukakis' loss to George H. W. Bush.)

After the election, Johnson found himself powerless. He initially attempted to transfer the authority of Senate majority leader to the vice presidency, since that office made him president of the Senate, but faced vehement opposition from the Democratic Caucus, including members he had counted as his supporters. This episode led to a memorable quote from Johnson: I now know the difference between a caucus and a cactus: in a cactus, all the pricks are on the outside.

Johnson then also tried to gain advantage in the Executive Branch. Shortly after the inauguration, he sent a proposed executive order to the White House for Kennedy's signature, granting Johnson "general supervision" over matters of national security and requiring all government agencies to "cooperate fully with the vice president in the carrying out of these assignments." Kennedy's response was to sign a non-binding letter requesting Johnson to "review" national security policies instead. Kennedy similarly turned down early requests from Johnson to be given an office adjacent to the Oval Office, and to employ a full-time Vice Presidential staff within the White House. His lack of influence was thrown into relief later in 1961 when Kennedy appointed Johnson's friend Sarah T. Hughes to a federal judgeship; whereas Johnson had tried and failed to garner the nomination for Hughes at the beginning of his vice presidency, House Speaker Sam Rayburn wrangled the appointment from Kennedy in exchange for support of an administration bill.

Johnson then also tried to gain advantage in the Executive Branch. Shortly after the inauguration, he sent a proposed executive order to the White House for Kennedy's signature, granting Johnson "general supervision" over matters of national security and requiring all government agencies to "cooperate fully with the vice president in the carrying out of these assignments." Kennedy's response was to sign a non-binding letter requesting Johnson to "review" national security policies instead. Kennedy similarly turned down early requests from Johnson to be given an office adjacent to the Oval Office, and to employ a full-time Vice Presidential staff within the White House. His lack of influence was thrown into relief later in 1961 when Kennedy appointed Johnson's friend Sarah T. Hughes to a federal judgeship; whereas Johnson had tried and failed to garner the nomination for Hughes at the beginning of his vice presidency, House Speaker Sam Rayburn wrangled the appointment from Kennedy in exchange for support of an administration bill.Johnson was sworn in as President on Air Force One at Dallas Love Field in Dallas on November 22, 1963, two hours and eight minutes after President Kennedy was assassinated in Dealey Plaza in Dallas. He was sworn in by Federal Judge Sarah T. Hughes, a family friend, making him the first President sworn in by a woman. He is also the only President to have been sworn in on Texas soil. Johnson did not swear on a Bible, as there was none on Air Force One; a Roman Catholic missal was found in Kennedy's desk and was used for the swearing-in ceremony. Johnson being sworn in as president has become the most famous photo ever taken aboard a presidential aircraft.

In the days following the assassination, Lyndon B. Johnson made an address to Congress: "No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy's memory than the earliest possible passage of the Civil Rights Bill for which he fought so long." The wave of national grief following the assassination gave enormous momentum to Johnson's promise to carry out Kennedy's programs.

One week after the assassination, on November 29, Johnson issued an executive order to rename NASA's Apollo Launch Operations Center and the NASA/Air Force Cape Canaveral launch facilities as the John F. Kennedy Space Center. Canaveral became popularly known as "Cape Kennedy" for a decade.

On the same day, Johnson created a panel headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren, known as the Warren Commission, to investigate Kennedy's assassination. The commission conducted hearings and concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in the assassination. Not everyone agreed with the Warren Commission, and numerous public and private investigations continued for decades after Johnson left office.

Johnson retained senior Kennedy appointees, some for the full term of his presidency. The late President's brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, with whom Johnson had a notoriously difficult relationship, remained in office for a few months until leaving in 1964, to run for the Senate. Robert F. Kennedy has been quoted as saying that LBJ was "mean, bitter, vicious—[an] animal in many ways...I think his reactions on a lot of things are correct... but I think he's got this other side of him and his relationship with human beings which makes it difficult unless you want to 'kiss his behind' all the time. That is what Bob McNamara suggested to me...if I wanted to get along."[

Early in the 1964 presidential campaign, Barry Goldwater appeared to be a strong contender, especially because of support from the South, which threatened Johnson's position. However, Goldwater lost momentum as his campaign progressed. On September 7, 1964, Johnson's campaign managers broadcast the "Daisy ad". It portrayed a little girl picking petals from a daisy, counting up to ten. Then a baritone voice took over, counted down from ten to zero and the visual showed the explosion of a nuclear bomb. The message conveyed was that electing Goldwater president held the danger of nuclear war. Although it only aired one time, it became an issue during the campaign. Johnson won the presidency by a landslide, with 61.05 percent of the vote (the highest ever share of the popular vote) and the then-widest popular margin in the 20th century - more than 15.95 million votes (this was later surpassed by incumbent President Nixon's defeat of Senator McGovern in 1972).

Early in the 1964 presidential campaign, Barry Goldwater appeared to be a strong contender, especially because of support from the South, which threatened Johnson's position. However, Goldwater lost momentum as his campaign progressed. On September 7, 1964, Johnson's campaign managers broadcast the "Daisy ad". It portrayed a little girl picking petals from a daisy, counting up to ten. Then a baritone voice took over, counted down from ten to zero and the visual showed the explosion of a nuclear bomb. The message conveyed was that electing Goldwater president held the danger of nuclear war. Although it only aired one time, it became an issue during the campaign. Johnson won the presidency by a landslide, with 61.05 percent of the vote (the highest ever share of the popular vote) and the then-widest popular margin in the 20th century - more than 15.95 million votes (this was later surpassed by incumbent President Nixon's defeat of Senator McGovern in 1972).In mid-1964, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) was organized with the purpose of challenging Mississippi's all-white and anti-civil rights delegation to the Democratic National Convention of that year as not representative of all Mississippians. At the national convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey the MFDP claimed the seats for delegates for Mississippi, not on the grounds of the Party rules, but because the official Mississippi delegation had been elected by a primary conducted under Jim Crow laws in which blacks were excluded because of poll taxes, literacy tests, and even violence against black voters. The national Party's liberal leaders supported a compromise in which the white delegation and the MFDP would have an even division of the seats; Johnson was concerned that, while the regular Democrats of Mississippi would probably vote for Goldwater anyway, if the Democratic Party rejected the regular Democrats, he would lose the Democratic Party political structure that he needed to win in the South. Eventually, Hubert Humphrey, Walter Reuther and black civil rights leaders (including Roy Wilkins, Martin Luther King, and Bayard Rustin) worked out a compromise with MFDP leaders: the MFDP would receive two non-voting seats on the floor of the Convention; the regular Mississippi delegation would be required to pledge to support the party ticket; and no future Democratic convention would accept a delegation chosen by a discriminatory poll. When the leaders took the proposal back to the 64 members who had made the bus trip to Atlantic City, they voted it down. As MFDP Vice Chair Fannie Lou Hamer said, "We didn't come all the way up here to compromise for no more than we'd gotten here. We didn't come all this way for no two seats, 'cause all of us is tired." The failure of the compromise effort allowed the rest of the Democratic Party to conclude that the MFDP was simply being unreasonable, and they lost a great deal of their liberal support. After that, the convention went smoothly for Johnson without a searing battle over civil rights. Despite the landslide victory, Johnson, who carried the South as a whole in the election, lost the Deep South states of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia and South Carolina, the first time a Democratic candidate had done so since Reconstruction.

Johnson began his elected presidential term, ready to fulfill his earlier commitment to "carry forward the plans and programs of John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Not because of our sorrow or sympathy, but because they are right.

In conjunction with the Civil Rights Movement, Johnson overcame southern resistance and convinced the Democratic-Controlled Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed most forms of racial segregation. John F. Kennedy originally proposed the civil rights bill in June 1963. In late October 1963, Kennedy officially called the House leaders to the White House to line up the necessary votes for passage. After Kennedy's death, Johnson took the initiative in finishing what Kennedy started and broke a filibuster by Southern Democrats in March 1964; as a result, this pushed the bill for passage in the Senate. Johnson signed the revised and stronger bill into law on July 2, 1964. Legend has it that, as he put down his pen, Johnson told an aide, "We have lost the South for a generation", anticipating a coming backlash from Southern whites against Johnson's Democratic Party. Moreover, Richard Nixon politically counterattacked with the Southern Strategy where it would "secure" votes for the Republican Party by grabbing the advocates of segregation as well as most of the Southern Democrats.

In conjunction with the Civil Rights Movement, Johnson overcame southern resistance and convinced the Democratic-Controlled Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed most forms of racial segregation. John F. Kennedy originally proposed the civil rights bill in June 1963. In late October 1963, Kennedy officially called the House leaders to the White House to line up the necessary votes for passage. After Kennedy's death, Johnson took the initiative in finishing what Kennedy started and broke a filibuster by Southern Democrats in March 1964; as a result, this pushed the bill for passage in the Senate. Johnson signed the revised and stronger bill into law on July 2, 1964. Legend has it that, as he put down his pen, Johnson told an aide, "We have lost the South for a generation", anticipating a coming backlash from Southern whites against Johnson's Democratic Party. Moreover, Richard Nixon politically counterattacked with the Southern Strategy where it would "secure" votes for the Republican Party by grabbing the advocates of segregation as well as most of the Southern Democrats.In 1965, he achieved passage of a second civil rights bill, the Voting Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination in voting, thus allowing millions of southern blacks to vote for the first time. In accordance with the act, several states, "seven of the eleven southern states of the former confederacy" – Alabama, South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Virginia - were subjected to the procedure of preclearance in 1965, while Texas, home to the majority of the African American population at the time, followed in 1975.

Johnson signed the Immigration Act of 1965, which substantially changed U.S. immigration policy toward non-Europeans. According to OECD, "While European-born immigrants accounted for nearly 60% of the total foreign-born population in 1970, they accounted for only 15% in 2000." Immigration doubled between 1965 and 1970, and doubled again between 1970 and 1990. Since the liberalization of immigration policy in 1965, the number of first-generation immigrants living in the United States has quadrupled, from 9.6 million in 1970, to about 38 million in 2007.

The Great Society program, with its name coined from one of Johnson's speeches, became Johnson's agenda for Congress in January 1965: aid to education, attack on disease, Medicare, Medicaid, urban renewal, beautification, conservation, development of depressed regions, a wide-scale fight against poverty, control and prevention of crime, and removal of obstacles to the right to vote. Congress, at times augmenting or amending, enacted most of Johnson's recommendations. Johnson's achievements in social policy were made possible by liberal strength, especially after the Democratic landslide of 1964.

After the Great Society legislation of the 1960s, for the first time a person who was not elderly or disabled could receive need-based aid from the U.S. government.

In 1964, upon Johnson's request, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1964 and the Economic Opportunity Act, which was in association with the war on poverty. Johnson set in motion bills and acts, creating programs such as Head Start, food stamps, Work Study, Medicare and Medicaid.

The Medicare program was established on July 30, 1965, to offer cheaper medical services to the elderly, today covering tens of millions of Americans. Johnson gave the first two Medicare cards to former President Harry S Truman and his wife Bess after signing the Medicare bill at the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri.

The Medicare program was established on July 30, 1965, to offer cheaper medical services to the elderly, today covering tens of millions of Americans. Johnson gave the first two Medicare cards to former President Harry S Truman and his wife Bess after signing the Medicare bill at the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri. Lower income groups receive government-sponsored medical coverage through the Medicaid program.

During Johnson's years in office, national poverty declined significantly, with the percentage of Americans living below the poverty line dropping from 23% to 12%.

In 1965, Johnson signed the Coinage Act of 1965, changing the metal composition of US coins and calling silver a "scarce material".

On October 22, 1968, Lyndon Johnson signed the Gun Control Act of 1968, one of the largest and farthest-reaching federal gun control laws in American history. Much of the motivation for this large expansion of federal gun regulations came as a response to the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr..

During Johnson's administration, NASA conducted the Gemini manned space program, developed the Saturn V rocket and its launch facility, and prepared to make the first manned Apollo program flights. On January 27, 1967, the nation was stunned when the entire crew of Apollo 1 was killed in a cabin fire during a spacecraft test on the launch pad, stopping Apollo in its tracks. Rather than appointing another Warren-style commission, Johnson accepted Administrator James E. Webb's request for NASA to do its own investigation, holding itself accountable to Congress and the President. Johnson maintained his staunch support of Apollo through Congressional and press controversy, and the program recovered. The first two manned missions, Apollo 7 and the first manned flight to the Moon, Apollo 8, were completed by the end of Johnson's term. He congratulated the Apollo 8 crew, saying, "You've taken ... all of us, all over the world, into a new era." On July 16, 1969, Johnson attended the launch of the first Moon landing mission Apollo 11, becoming the first former or incumbent US president to witness a rocket launch.

Major riots in black neighborhoods caused a series of "long hot summers." They started with a violent disturbance in Harlem riots in 1964, and the Watts district of Los Angeles in 1965, and extended to 1971. The biggest wave came in April 1968, when riots occurred in over a hundred cities in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King. Newark burned in 1967, where six days of rioting left 26 dead, 1500 injured, and the inner city a burned out shell. In Detroit in 1967, Governor George Romney sent in 7400 national guard troops to quell fire bombings, looting, and attacks on businesses and on police. Johnson finally sent in federal troops with tanks and machine guns. Detroit continued to burn for three more days until finally 43 were dead, 2250 were injured, 4000 were arrested; property damage ranged into the hundreds of millions. Johnson called for even more billions to be spent in the cities and another federal civil rights law regarding housing, but his political capital had been spent, and his Great Society programs lost support. Johnson's popularity plummeted as a massive white political backlash took shape, reinforcing the sense Johnson had lost control of the streets of major cities as well as his party.[

Johnson created the Kerner Commission to study the problem of urban riots, headed by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner

Days after Johnson announced his withdrawal from the 1968 race, Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in Memphis. In the next week, Johnson faced one of the biggest wave of riots the nation had ever seen.

Johnson's problems began to mount in 1966. The press had sensed a "credibility gap" between what Johnson was saying in press conferences and what was happening on the ground in Vietnam, which led to much less favorable coverage of Johnson.

By year's end, the Democratic governor of Missouri, Warren E. Hearnes, warned that Johnson would lose the state by 100,000 votes, despite a half-million margin in 1964. "Frustration over Vietnam; too much federal spending and... taxation; no great public support for your Great Society programs; and ... public disenchantment with the civil rights programs" had eroded the President's standing, the governor reported. There were bright spots; in January 1967, Johnson boasted that wages were the highest in history, unemployment was at a 13-year low, and corporate profits and farm incomes were greater than ever; a 4.5 percent jump in consumer prices was worrisome, as was the rise in interest rates. Johnson asked for a temporary 6 percent surcharge in income taxes to cover the mounting deficit caused by increased spending. Johnson's approval ratings stayed below 50 percent; by January 1967, the number of his strong supporters had plunged to 16 percent, from 25 percent four months before. He ran about even with Republican George Romney in trial matchups that spring. Asked to explain why he was unpopular, Johnson responded, "I am a dominating personality, and when I get things done I don't always please all the people." Johnson also blamed the press, saying they showed "complete irresponsibility and lie and misstate facts and have no one to be answerable to." He also blamed "the preachers, liberals and professors" who had turned against him. In the congressional elections of 1966, the Republicans gained three seats in the Senate and 47 in the House, reinvigorating the conservative coalition and making it more difficult for Johnson to pass any additional Great Society legislation. However, in the end Congress passed almost 96 percent of the administration's Great Society programs, which Johnson then signed into law.

Johnson became the first serving U.S. president to visit Australia. His visit sparked demonstrations from anti-war protesters.

Johnson increasingly focused on the American military effort in Vietnam. He firmly believed in the Domino Theory and that his containment policy required America to make a serious effort to stop all Communist expansion. At Kennedy's death, there were 16,000 American military advisors in Vietnam. As President, Lyndon Johnson immediately reversed his predecessor's order to withdraw 1,000 military personnel by the end of 1963 with his own NSAM No. 273 on November 26, 1963. Johnson expanded the numbers and roles of the American military following the Gulf of Tonkin Incident (less than three weeks after the Republican Convention of 1964, which had nominated Barry Goldwater for President).

Johnson increasingly focused on the American military effort in Vietnam. He firmly believed in the Domino Theory and that his containment policy required America to make a serious effort to stop all Communist expansion. At Kennedy's death, there were 16,000 American military advisors in Vietnam. As President, Lyndon Johnson immediately reversed his predecessor's order to withdraw 1,000 military personnel by the end of 1963 with his own NSAM No. 273 on November 26, 1963. Johnson expanded the numbers and roles of the American military following the Gulf of Tonkin Incident (less than three weeks after the Republican Convention of 1964, which had nominated Barry Goldwater for President).Politically, Johnson closely watched the public opinion polls. His goal was not to adjust his policies to follow opinion, but rather to adjust opinion to support his policies. Until the Tet Offensive of 1968, he systematically downplayed the war; he made very few speeches about Vietnam, and held no rallies or parades or advertising campaigns. He feared that publicity would charge up the hawks who wanted victory, and weaken both his containment policy and his higher priorities in domestic issues.

Additionally, domestic issues were driving his polls down steadily from spring 1966 onward. A few analysts have theorized that "Vietnam had no independent impact on President Johnson's popularity at all after other effects, including a general overall downward trend in popularity, had been taken into account." The war grew less popular, and continued to split the Democratic Party. The Republican Party was not completely pro or anti-war, and Nixon managed to get support from both groups by running on a reduction in troop levels with an eye toward eventually ending the campaign.

He often privately cursed the Vietnam War, and in a conversation with Robert McNamara, Johnson assailed "the bunch of commies" running The New York Times for their articles against the war effort. Johnson believed that America could not afford to lose and risk appearing weak in the eyes of the world. In a discussion about the war with former President Dwight Eisenhower on October 3, 1966, Johnson said he was "trying to win it just as fast as I can in every way that I know how" and later stated that he needed "all the help I can get." Johnson escalated the war effort continuously from 1964 to 1968, and the number of American deaths rose. In two weeks in May 1968 alone American deaths numbered 1,800 with total casualties at 18,000. Alluding to the Domino Theory, he said, "If we allow Vietnam to fall, tomorrow we'll be fighting in Hawaii, and next week in San Francisco."

Johnson was afraid that if he tried to defeat the North Vietnamese regime with an invasion of North Vietnam, rather than simply try to protect South Vietnam, he might provoke the Chinese to stage a full-scale military intervention similar to their intervention in 1950 during the Korean War, as well as provoke the Soviets into launching a full-scale military invasion of western Europe. It was not until the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s that it was finally confirmed that the Soviets had several thousand troops stationed in North Vietnam throughout the conflict, as did China.

During his presidency, Johnson issued 1187 pardons and commutations, granting over 20 percent of such requests.

As he had served less than 24 months of President Kennedy's term, Johnson was constitutionally permitted to run for a second full term in the 1968 presidential election under the provisions of the 22nd Amendment. Initially, no prominent Democratic candidate was prepared to run against a sitting president of the Democratic party. Only Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota challenged Johnson as an anti-war candidate in the New Hampshire primary, hoping to pressure the Democrats to oppose the Vietnam War. On March 12, McCarthy won 42 percent of the primary vote to Johnson's 49 percent, an amazingly strong showing for such a challenger. Four days later, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy of New York entered the race. Internal polling by Johnson's campaign in Wisconsin, the next state to hold a primary election, showed the President trailing badly. Johnson did not leave the White House to campaign.

By this time Johnson had lost control of the Democratic Party, which was splitting into four factions, each of which despised the other three. The first consisted of Johnson (and Humphrey), labor unions, and local party bosses (led by Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley). The second group consisted of students and intellectuals who were vociferously against the war and rallied behind McCarthy. The third group were Catholics, Hispanics and African Americans, who rallied behind Robert Kennedy. The fourth group were traditionally segregationist white Southerners, who rallied behind George C. Wallace and the American Independent Party. Vietnam was one of many issues that splintered the party, and Johnson could see no way to win the war and no way to unite the party long enough for him to win re-election.

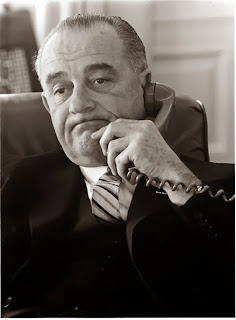

Johnson was often seen as a wildly ambitious, tireless, and imposing figure who was ruthlessly effective at getting legislation passed. He worked 18–20-hour days without break and was apparently absent of any leisure activities. "There was no more powerful majority leader in American history," biographer Robert Dallek writes. Dallek stated that Johnson had biographies on all the Senators, knew what their ambitions, hopes, and tastes were and used it to his advantage in securing votes. Another Johnson biographer noted, "He could get up every day and learn what their fears, their desires, their wishes, their wants were and he could then manipulate, dominate, persuade and cajole them." At 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m) tall, Johnson had his own particular brand of persuasion, known as "The Johnson Treatment". A contemporary writes, "It was an incredible blend of badgering, cajolery, reminders of past favors, promises of future favors, predictions of gloom if something doesn't happen. When that man started to work on you, all of a sudden, you just felt that you were standing under a waterfall and the stuff was pouring on you."

Johnson was often seen as a wildly ambitious, tireless, and imposing figure who was ruthlessly effective at getting legislation passed. He worked 18–20-hour days without break and was apparently absent of any leisure activities. "There was no more powerful majority leader in American history," biographer Robert Dallek writes. Dallek stated that Johnson had biographies on all the Senators, knew what their ambitions, hopes, and tastes were and used it to his advantage in securing votes. Another Johnson biographer noted, "He could get up every day and learn what their fears, their desires, their wishes, their wants were and he could then manipulate, dominate, persuade and cajole them." At 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m) tall, Johnson had his own particular brand of persuasion, known as "The Johnson Treatment". A contemporary writes, "It was an incredible blend of badgering, cajolery, reminders of past favors, promises of future favors, predictions of gloom if something doesn't happen. When that man started to work on you, all of a sudden, you just felt that you were standing under a waterfall and the stuff was pouring on you."Johnson's cowboy hat and boots reflected his Texas roots and genuine love of the rural hill country. From 250 acres (100 ha) of land that he was given by an aunt in 1951, he created a 2,700-acre working ranch with 400 head of registered Hereford cattle. The National Park Service keeps a herd of Hereford cattle descended from Johnson's registered herd and maintains the ranch property.

After leaving the presidency in January 1969, Johnson went home to his ranch in Stonewall, Texas, accompanied by former Aide and speech writer Harry J. Middleton, who would draft Johnson's first book, The Choices We Face, and work with him on his memoirs entitled The Vantage Point: Perspectives of the Presidency 1963-1969, published in 1971.

In March 1970, Johnson was hospitalized at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, after suffering an attack of angina. He was urged to lose considerable weight. He had grown dangerously heavier since leaving the White House, gaining more than 25 pounds (11 kg) and weighing around 235 pounds (107 kg). The following summer, again gripped by chest pains, he embarked on a crash water diet, shedding about 15 pounds (6.8 kg) in less than a month. In April 1972, Johnson experienced a massive heart attack while visiting his daughter, Lynda, in Charlottesville, Virginia. "I'm hurting real bad," he confided to friends. The chest pains hit him nearly every afternoon – a series of sharp, jolting pains that left him scared and breathless. A portable oxygen tank stood next to his bed, and he periodically interrupted what he was doing to lie down and don the mask to gulp air. He continued to smoke heavily, and, although placed on a low-calorie, low-cholesterol diet, kept to it only in fits and starts. Meanwhile, he began experiencing severe stomach pains. Doctors diagnosed this problem as diverticulosis, pouches forming on the intestine. Also symptomatic of the aging process, the condition rapidly worsened and surgery was recommended. Johnson flew to Houston to consult with heart specialist Dr. Michael DeBakey, who decided that Johnson's heart condition presented too great a risk for any sort of surgery, including coronary bypass of two almost totally destroyed heart arteries.

Johnson died at his ranch at 3:39 p.m CST on January 22, 1973, at age 64 after suffering a massive heart attack. His death came the day before a ceasefire was signed in Vietnam and just a month after former president Harry S. Truman died. (Truman's funeral on December 28, 1972 had been one of Johnson's last public appearances). His death also occurred just two days after the end of what would have been his final term in office had he successfully won reelection in 1968. His health had been affected by years of heavy smoking, poor diet, and extreme stress; the former president had advanced coronary artery disease. He had his first, nearly fatal, heart attack in July 1955 and suffered a second one in April 1972, but had been unable to quit smoking after he left the Oval Office in 1969. He was found dead by Secret Service agents, in his bed, with a telephone receiver in his hand. The agents were responding to a desperate call Johnson had made to the Secret Service compound on his ranch minutes earlier complaining of "massive chest pains".

Johnson died at his ranch at 3:39 p.m CST on January 22, 1973, at age 64 after suffering a massive heart attack. His death came the day before a ceasefire was signed in Vietnam and just a month after former president Harry S. Truman died. (Truman's funeral on December 28, 1972 had been one of Johnson's last public appearances). His death also occurred just two days after the end of what would have been his final term in office had he successfully won reelection in 1968. His health had been affected by years of heavy smoking, poor diet, and extreme stress; the former president had advanced coronary artery disease. He had his first, nearly fatal, heart attack in July 1955 and suffered a second one in April 1972, but had been unable to quit smoking after he left the Oval Office in 1969. He was found dead by Secret Service agents, in his bed, with a telephone receiver in his hand. The agents were responding to a desperate call Johnson had made to the Secret Service compound on his ranch minutes earlier complaining of "massive chest pains".Shortly after Johnson's death, his press secretary Tom Johnson (no relation to Johnson), telephoned Walter Cronkite at CBS; Cronkite was live on the air with the CBS Evening News at the time, and a report on Vietnam was cut abruptly while Cronkite was still on the line, so he could break the news.

Sources: Wikipedia

This work released through CC 3.0 BY-SA - Creative Commons

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.