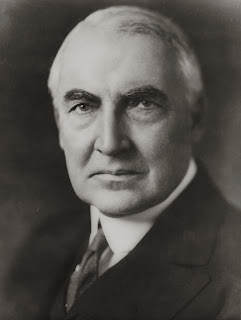

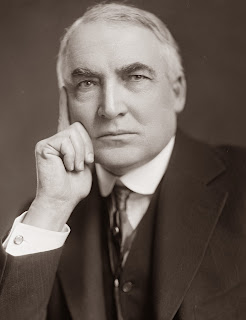

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th President of the United States (1921–1923), a Republican from Ohio who served in the Ohio Senate and then in the United States Senate where he protected alcohol interests and moderately supported women's suffrage. He was the first incumbent U.S. senator and (self-made) newspaper publisher to be elected U.S. president.

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th President of the United States (1921–1923), a Republican from Ohio who served in the Ohio Senate and then in the United States Senate where he protected alcohol interests and moderately supported women's suffrage. He was the first incumbent U.S. senator and (self-made) newspaper publisher to be elected U.S. president.Harding was the compromise candidate in the 1920 election, when he promised the nation a return to "normalcy", in the form of a strong economy, independent of foreign influence. This program was designed to rid Americans of the tragic memories and hardships faced during World War I. Harding and the Republican Party had desired to move away from progressivism that dominated the early 20th century. He defeated Democrat and fellow Ohioan James M. Cox in the largest presidential popular vote landslide (60.32% to 34.15%) since popular vote totals were first recorded.

Harding not only put the "best minds" on his cabinet including Herbert Hoover as Secretary of Commerce and Charles Evans Hughes as Secretary of State, but also rewarded his friends and contributors, known as the Ohio Gang, with powerful positions. Cases of corruption, including the notorious Teapot Dome scandal, arose resulting in prison terms for his appointees. He was a keen poker player, who once gambled away on a single hand an entire set of White House china dating back to Benjamin Harrison. Harding did manage to clean up corruption in the Veterans Bureau.

Domestically, Harding signed the first federal child welfare program, dealt with striking mining and railroad workers, including supporting an 8-hour work day, and attended an unemployment rate drop by half. He also set up the Bureau of the Budget to prepare the United States federal budget.

Harding advocated an anti-lynching bill to curb violence against African Americans; it failed to pass. In foreign affairs, Harding spurned the League of Nations, and (Congress having rejected the Treaty of Versailles) signed a World War I peace treaty with Germany and Austria separate from the other Allies. Harding promoted a successful world naval program.

In August 1923, Harding suddenly collapsed and died. His administration's many scandals have historically earned Harding a low ranking as president, but there has been growing recognition of his fiscal responsibility and endorsement of African-American civil rights. Harding has been viewed as a more modern politician who embraced technology and who was sensitive to the plights of minorities, women, and labor.

Warren Gamaliel Harding was born November 2, 1865, in Blooming Grove, Ohio. His paternal ancestors, mostly ardent Baptists, hailed from Clifford, Pennsylvania and had migrated to Ohio in 1820.

Nicknamed "Winnie", he was the eldest of eight children born to Dr.

George Tryon Harding, Sr. (1843–1928) and Phoebe Elizabeth (Dickerson)

Harding (1843–1910).

His mother, a devout Methodist, was a midwife who later obtained her

medical license. His father, never quite content with his current job or

possessions, was forever swapping for something better, and was usually

in debt; he owned a farm, taught at a rural school north of Mount Gilead, Ohio, and also acquired a medical degree and started a small practice. It was rumored in Blooming Grove that one of Harding's great-grandmothers might have been African American.

Warren Gamaliel Harding was born November 2, 1865, in Blooming Grove, Ohio. His paternal ancestors, mostly ardent Baptists, hailed from Clifford, Pennsylvania and had migrated to Ohio in 1820.

Nicknamed "Winnie", he was the eldest of eight children born to Dr.

George Tryon Harding, Sr. (1843–1928) and Phoebe Elizabeth (Dickerson)

Harding (1843–1910).

His mother, a devout Methodist, was a midwife who later obtained her

medical license. His father, never quite content with his current job or

possessions, was forever swapping for something better, and was usually

in debt; he owned a farm, taught at a rural school north of Mount Gilead, Ohio, and also acquired a medical degree and started a small practice. It was rumored in Blooming Grove that one of Harding's great-grandmothers might have been African American.Harding's great-great grandfather Amos claimed that a thief, who had been caught in the act by the family, started the rumor as an attempted extortion. Eventually, Harding's family moved to Caledonia, Ohio, where his father then acquired The Argus, a local weekly newspaper. It was at The Argus where, from the age of 10, Harding learned the basics of the journalism business. In 1878, his brother Charles and sister Persilla died, presumably from typhoid.

Harding continued to study the printing and newspaper trade as a college student at Ohio Central College in Iberia. At the same time, he worked at the Union Register in Mount Gilead. Harding became an accomplished public speaker in college, and graduated in 1882 at the age of 17 with a Bachelor of Science degree. As a youngster, Harding had become an accomplished cornet player and played in various bands. In 1884, Harding gained popular recognition in Marion, when his Citizens' Cornet Band won the third place $200 prize at the highly competitive Ohio State Band Festival in Findlay. The prize money paid for the band's snappy dress uniforms Harding had bought on credit.

On July 8, 1891, Harding married Florence Kling DeWolfe, the daughter of his nemesis (and hers as well), Amos Hall Kling. Florence Kling DeWolfe was a divorcée, five years Harding's senior, and the mother of a young son, Marshall Eugene DeWolfe. "Flossie's" first, and compulsory, marriage, to an alcoholic, had been soundly condemned by her father, to the point of her disownment. Her mother remained loyal and provided support nevertheless. She pursued Harding persistently, until he reluctantly proposed. On his part, according to noted biographer Russell, true love was missing, but the prospect of social acceptance, and standing, was the compelling reason for his proposal.

Florence's father was incensed by his daughter's decision to marry Harding, prohibited his wife from attending the wedding (she sneaked in long enough to see the vows exchanged) and refused to speak to his daughter or son-in-law for eight years. Her mother continued to provide support on the sly.

The couple was complementary, with Harding's affable personality balancing his wife's no-nonsense approach to life. Florence Harding, exhibiting her father's determination and business sense, turned the Marion Daily Star into a profitable business in her management of the circulation. She has been credited with helping Harding achieve more than he might have alone; some have speculated that she later pushed him all the way to the White House. Early in their marriage, Harding bestowed on her the lasting nickname "Duchess" as a nod to the imperious (and often alienating) persona she shared with her father.

In the 1920 election, Harding ran against Democratic Ohio Governor James M. Cox, whose running mate was Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. The election was seen in part as a rejection of the "progressive" ideology of the Woodrow Wilson Administration in favor of the "laissez-faire" approach of the William McKinley era.

In the 1920 election, Harding ran against Democratic Ohio Governor James M. Cox, whose running mate was Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. The election was seen in part as a rejection of the "progressive" ideology of the Woodrow Wilson Administration in favor of the "laissez-faire" approach of the William McKinley era.Harding ran on a promise to "Return to Normalcy", a seldom-used term he popularized, and healing for the nation after World War I. The policy called for an end to the abnormal era of the Great War, along with a call to reflect three trends of the time: a renewed isolationism in reaction to the War, a resurgence of nativism, and a turning away from government activism.

On July 28, 1920, Harding's general election campaign manager, Albert Lasker, unleashed a broad-based advertising campaign that implemented modern advertising techniques; the focus was more strategy oriented. Lasker's approach included newsreels and sound recordings, all in an effort to enhance Harding's patriotism and affability. Farmers were sent brochures decrying the alleged abuses of Democratic agriculture policies. African Americans and women were also given literature in an attempt to take away votes from the Democrats. Professional advertisers including Chicagoan Albert Tucker were consulted. Billboard posters, newspapers and magazines were employed in addition to motion pictures. Five thousand speakers were trained by advertiser Harry New and sent abroad to speak for Harding; 2,000 of these speakers were women. Telemarketers were used to make phone conferences with perfected dialogues to promote Harding. Lasker had 8,000 photos distributed around the nation every two weeks of Harding and his wife.

Harding's "front porch campaign" during the late summer and fall of 1920 captured the imagination of the country. Not only was it the first campaign to be heavily covered by the press and to receive widespread newsreel coverage, but it was also the first modern campaign to use the power of Hollywood and Broadway stars, who travelled to Marion for photo opportunities with Harding and his wife. Al Jolson, Lillian Russell, Douglas Fairbanks, and Mary Pickford were among the luminaries to make the pilgrimage to his house in central Ohio. Business icons Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Harvey Firestone also lent their cachet to the campaign. From the onset of the campaign until the November election, over 600,000 people travelled to Marion to participate.

The campaign owed a great deal to Florence Harding, who played a more active role than the wives of previous candidates had. She cultivated the relationship between the campaign and the press. As the business manager of the Star, she understood reporters and their industry. She played to their needs by being available to answer questions, pose for pictures, or deliver food from her kitchen to the press office - a bungalow that she had constructed at the rear of their property in Marion. Mrs. Harding even coached her husband on the proper way to wave to newsreel cameras to make the most of coverage.

Campaign manager Lasker struck a deal with Harding's paramour, Carrie Phillips, and her husband Jim Phillips, whereby the couple agreed to leave the country until after the election. Ostensibly, Mr. Phillips was to investigate the silk trade.

The campaign also drew on Harding's popularity with women. Considered handsome, Harding photographed well compared to Cox. However, it was mainly Harding's Senate support for women's suffrage legislation that made him popular in that demographic. Ratification of the 19th Amendment in August 1920 brought huge crowds of women to Marion, Ohio to hear Harding speak. Immigrant groups such such as ethnic Germans and Irish, who made up an important part of the Democratic coalition, also voted for Harding - in reaction to their perceived persecution by the Wilson administration during World War I.

The 1920 election was the first in which women could vote nationwide. It

was also the first presidential election covered on the radio, thanks

to both 8ZZ (later KDKA in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) and 8MK (later WWJ)

in Detroit, which carried the election returns - as did the educational

and amateur radio station 1XE (later WGI) at Medford Hillside MA.

Harding received 60% of the national vote, the highest percentage ever

recorded up to that time, and 404 electoral votes. Cox received 34% of the national vote and 127 electoral votes.

The 1920 election was the first in which women could vote nationwide. It

was also the first presidential election covered on the radio, thanks

to both 8ZZ (later KDKA in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) and 8MK (later WWJ)

in Detroit, which carried the election returns - as did the educational

and amateur radio station 1XE (later WGI) at Medford Hillside MA.

Harding received 60% of the national vote, the highest percentage ever

recorded up to that time, and 404 electoral votes. Cox received 34% of the national vote and 127 electoral votes.Campaigning from a federal prison, Socialist Eugene V. Debs received 3% of the national vote. The Presidential election results of 1920, for the first time in U.S. history, were announced live by radio. Harding was the only Republican presidential candidate to ever defeat Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt on a presidential ticket. At the same time, the Republicans picked up an astounding 63 seats in the House of Representatives. Harding immediately embarked on a vacation that included an inspection tour of facilities in the Panama Canal Zone.

Harding preferred a low-key inauguration, without the customary parade, leaving only the swearing-in ceremony and a brief reception at the White House. In his inaugural speech he declared, "Our most dangerous tendency is to expect too much from the government and at the same time do too little for it." The Hardings also brought a different style to the running of the White House. Though Mrs. Harding did keep a little red book of those who had offended her, the executive mansion was now once again open to the public, including the annual Easter egg roll.

The administration of Warren G. Harding followed the Republican platform approved at the 1920 Republican National Convention, which was held in Chicago. Harding, who had been elected by a landslide, felt the "pulse" of the nation and for the 28 months in office he remained popular both nationally and internationally. Harding's administration has been critically viewed due to multiple scandals, while his successes in office were often given credit to his capable cabinet appointments that included future President Herbert Hoover. Author Wayne Lutton asked, "Was Harding really a failure?" Historian and former White House Counsel John Dean's reassessment of Harding stated his accomplishments included income tax and federal spending reductions, economic policies that reduced "stagflation", a reduction of unemployment by 10%, and a bold foreign policy that created peace with Germany, Japan, and Central America. Herbert Hoover, while serving in Harding's cabinet, was confident the President would serve two terms and return the world to normality. Later, in his own memoirs, he stated that Harding had "neither the experience nor the intellect that the position needed."

Harding pushed for the establishment of the Bureau of Veterans Affairs (later organized as the Department of Veterans Affairs), the first permanent attempt at answering the needs of those who had served the nation in time of war.

In April 1921, Harding spoke before a special joint session of Congress

that he had called. He argued for peacemaking with Germany and Austria,

emergency tariffs,

new immigration laws, regulation of radio and trans-cable

communications, retrenchment in government, tax reduction, repeal of

wartime excess profits tax, reduction of railroad rates, promotion of

agricultural interests, a national budget system, an enlarged merchant marine, and a department of public welfare. He also called for measures to end lynching, but not wanting to make enemies in his own party and with the Democrats, he did not fight for his program.

Generally, there was a lack of strong leadership in the Congress and,

unlike his predecessors Roosevelt and Wilson, Harding was not inclined

to fill that void.

Harding pushed for the establishment of the Bureau of Veterans Affairs (later organized as the Department of Veterans Affairs), the first permanent attempt at answering the needs of those who had served the nation in time of war.

In April 1921, Harding spoke before a special joint session of Congress

that he had called. He argued for peacemaking with Germany and Austria,

emergency tariffs,

new immigration laws, regulation of radio and trans-cable

communications, retrenchment in government, tax reduction, repeal of

wartime excess profits tax, reduction of railroad rates, promotion of

agricultural interests, a national budget system, an enlarged merchant marine, and a department of public welfare. He also called for measures to end lynching, but not wanting to make enemies in his own party and with the Democrats, he did not fight for his program.

Generally, there was a lack of strong leadership in the Congress and,

unlike his predecessors Roosevelt and Wilson, Harding was not inclined

to fill that void. On December 23, 1921 Harding calmed the 1919–1920 Bolshevik scare, and released an election opponent, socialist leader Eugene Debs, from prison. This was part of an effort to return the United States to "normalcy" after the Great War. Debs, a forceful World War I antiwar activist, had been convicted under sedition charges brought by the Wilson administration for his opposition to the draft during World War I. Despite many political differences between the two candidates Harding commuted Debs' sentence to time served; however, he was not granted an official Presidential pardon. Debs' failing health was a contributing factor for the release. Harding granted a general amnesty to 23 prisoners, alleged anarchists and socialists, active in the Red Scare.

On March 4, Harding assumed office while the nation was in the midst of a postwar economic decline, known as the Depression of 1920–21. By summer of his first year in office, an economic recovery began.

Harding convened the Conference of Unemployment in 1921, headed by Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, that proactively advocated stimulating the economy with local public work projects and encouraged businesses to apply shared work programs.

Harding's Treasury Secretary, Andrew Mellon, ordered a study that claimed to demonstrate that as income tax rates were increased, money was driven underground or abroad. Mellon concluded that lower rates would increase tax revenues. Based on this advice, Harding cut taxes, starting in 1922. The top marginal rate was reduced annually in four stages from 73% in 1921 to 25% in 1925. Taxes were cut for lower incomes starting in 1923.

Revenues to the treasury increased substantially. Unemployment also continued to fall. Libertarian historian Thomas Woods contends that the tax cuts ended the Depression of 1920–1921 and were responsible for creating a decade-long expansion. Historians Schweikart and Allen attribute these changes to the tax cuts. Schweikart and Allen also argue that Harding's tax and economic policies in part "... produced the most vibrant eight year burst of manufacturing and innovation in the nation's history." The combined declines in unemployment and inflation (later known as the Misery Index) were among the sharpest in U.S. history. Wages, profits, and productivity all made substantial gains during the 1920s.

Harding was tolerant towards religious faiths. Harding appointed

prominent Jewish leader, Rabbi Joseph S. Kornfeld, and Catholic leader,

Father Joseph M. Dennig, to foreign diplomatic positions. Harding also

appointed Albert Lasker,

a Jewish businessman and Harding's 1920 Presidential campaign manager,

head of the Shipping Department. In an unpublished letter, Harding

advocated the establishment and funding of a Jewish homeland in

Palestine.

Harding was tolerant towards religious faiths. Harding appointed

prominent Jewish leader, Rabbi Joseph S. Kornfeld, and Catholic leader,

Father Joseph M. Dennig, to foreign diplomatic positions. Harding also

appointed Albert Lasker,

a Jewish businessman and Harding's 1920 Presidential campaign manager,

head of the Shipping Department. In an unpublished letter, Harding

advocated the establishment and funding of a Jewish homeland in

Palestine. Harding's lifestyle at the White House was fairly unconventional compared to his predecessor President Woodrow Wilson. Upstairs at the White House, in the Yellow Oval Room, Harding allowed bootleg whiskey to be freely served to his guests during after-dinner parties at a time when the President was supposed to enforce Prohibition. One witness, Alice Longworth, daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt, claimed that trays, "...with bottles containing every imaginable brand of whiskey stood about." Some of this alcohol had been directly confiscated from the Prohibition department by Jess Smith, assistant to U.S. Attorney General Harry Daugherty. Mrs. Harding, also known as the "Duchess", mixed drinks for the guests. Harding also indulged in poker playing twice a week, smoking, and chewing tobacco. Harding allegedly won a $4,000 pearl necktie pin at one White House poker game. Although criticized by Prohibitionist advocate Wayne B. Wheeler over Washington, D.C. rumors of these "wild parties", Harding claimed his personal drinking inside the White House was his own business.

In June 1923, Harding set out on a westward cross-country Voyage of Understanding,

in which he planned to renew his connection with the people, away from

the capital, and explain his policies. The schedule included 18 speeches

and innumerable informal talks. Accompanying him were Secretaries Work,

Wallace, and Hoover, House Speaker Gillett, and Rear Admiral Adam Hugh

Rodman. During this trip, he became the first president to visit Alaska.

In June 1923, Harding set out on a westward cross-country Voyage of Understanding,

in which he planned to renew his connection with the people, away from

the capital, and explain his policies. The schedule included 18 speeches

and innumerable informal talks. Accompanying him were Secretaries Work,

Wallace, and Hoover, House Speaker Gillett, and Rear Admiral Adam Hugh

Rodman. During this trip, he became the first president to visit Alaska.Harding's physical health had declined since the fall of 1922. One doctor, Emmanuel Libman, who met Harding at a dinner, privately suggested that the President was suffering from coronary disease. By early 1923, Harding had trouble sleeping, looked tired, and could barely get through nine holes of golf.

Though Harding wanted to run for a second term, he may have been aware of his own health decline. He gave up drinking, sold his "life-work," the Marion Star, in part to regain $170,000 previous investment losses, and had the U.S. Attorney General Harry Daugherty make a new will. Harding, along with his personal physician Dr. Charles E. Sawyer, believed getting away from Washington would help relieve the stresses of being President. By July 1923, criticism of the Harding Administration was increasing. Prior to his leaving Washington, the President reported chest pains that radiated down his left arm.

Harding's sudden death led to theories that he had been poisoned or committed suicide. Suicide appears unlikely, since Harding was planning for reelection in 1924. Rumors of poisoning were fueled, in part, by a book called The Strange Death of President Harding, in which the author (convicted criminal, former Ohio Gang member, and detective Gaston Means, hired by Mrs. Harding to investigate Warren Harding and his mistress) suggested that Mrs. Harding had poisoned her husband. Mrs. Harding's refusal to allow an autopsy on her husband only added to the speculation. According to the physicians attending Harding, however, the symptoms prior to his death all pointed to congestive heart failure. Harding's biographer, Samuel H. Adams, concluded that "Warren G. Harding died a natural death which, in any case, could not have been long postponed".

Immediately after Harding's death, Mrs. Harding returned to Washington, D.C., and stayed in the White House briefly with the Coolidges. For a month, former First Lady Harding gathered and burned President Harding's correspondence and documents, both official and unofficial. Upon her return to Marion, Mrs. Harding hired a number of secretaries to collect and burn Harding's personal papers. According to Mrs. Harding, she took these actions to protect her husband's legacy. The remaining papers were held and kept from public view by the Harding Memorial Association in Marion.

Sources: Wikipedia

This work released through CC 3.0 BY-SA- Creative Commons

I'm actually related to him on my Grandfather Bowers side. Harding was a cousin to my Great Grandma Bowers (Gernert). I've seen his original burial place which, was brick, before they moved he and his wife to the Presidential estate. Apparently, Great Grandma never wanted to talk about him much. If anyone has other information, I'd be interested in finding out more. I need to get to Marion sometime and just walk the grounds and see what is info is there.

ReplyDeleteThat's fantastic. I bet it's cool to be related to a president. Good luck in finding that info. And if anyone reading this has anymore info, feel free to leave it here in the comments section.

Delete