The flag of Jordan, officially adopted on April 18, 1928, is based on the flag of the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire during World War I. The flag consists of horizontal black, white, and green bands that are connected by a red chevron. The colors stand are the Pan-Arab Colors, representing the Abbasid (black band), Umayyad (white band), and Fatimid (green band) caliphates. The red chevron is for the Hashemite dynasty, and the Arab Revolt.

The seven-pointed star stands for the seven verses of the first surah in the Qur'an, and also stands for the unity of the Arab peoples. Some believe it also refers to the seven hills on which Amman, the capital, was built.

In addition to the bands and chevron, a white star with seven points is featured on the hoist side of the red chevron. The seven points symbolize the seven verses of Islamic belief, which is mentioned at the beginning of the Qur'an. The seven points represent faith in one God, humanity, humility, national spirit, virtue, social justice, and aspiration. The star also stands for the unity of the Arab nation.

Sources: Wikipedia

This work released through CC 3.0 BY-SA - Creative Commons

Sunday, March 30, 2014

Thursday, March 27, 2014

William Kidd: Pirates

Captain William Kidd (c. 22 January 1645 – 23 May 1701) was a Scottish sailor who was tried and executed for piracy after returning from a voyage to the Indian Ocean. Some modern historians deem his piratical reputation unjust, as there is evidence that Kidd acted only as a privateer. Kidd's fame springs largely from the sensational circumstances of his questioning before the English Parliament and the ensuing trial. His actual depredations on the high seas, whether piratical or not, were both less destructive and less lucrative than those of many other contemporary pirates and privateers.

Captain William Kidd (c. 22 January 1645 – 23 May 1701) was a Scottish sailor who was tried and executed for piracy after returning from a voyage to the Indian Ocean. Some modern historians deem his piratical reputation unjust, as there is evidence that Kidd acted only as a privateer. Kidd's fame springs largely from the sensational circumstances of his questioning before the English Parliament and the ensuing trial. His actual depredations on the high seas, whether piratical or not, were both less destructive and less lucrative than those of many other contemporary pirates and privateers.Kidd was born in Dundee, Scotland, January 1645. He gave the city as his place of birth and said he was aged 41 in testimony under oath at the High Court of the Admiralty in October 1695 or 1694. Researcher Dr David Dobson later identified his baptism documents from Dundee in 1645. His father was Captain John Kyd, who was lost at sea. A local society supported the family financially. Richard Zacks in the biography The Pirate Hunter (2002) says Kidd came from Dundee. Reports that Kidd came from Greenock have been dismissed by Dr. Dobson, who found neither the name Kidd nor Kyd in baptismal records. The myth that his "father was thought to have been a Church of Scotland minister" is also discounted. There is no mention of the name in comprehensive Church of Scotland records for the period. A contrary view is presented here Kidd later settled in the new colony of New York. It was here that he befriended many prominent colonial citizens, including three governors. There is some information that suggests he was a seaman's apprentice on a pirate ship much earlier than his own more famous seagoing exploits.

The first records of his life date from 1689, when he was a member of a French-English pirate crew that sailed in the Caribbean. Kidd and other members of the crew mutinied, ousted the captain of the ship, and sailed to the English colony of Nevis. There they renamed the ship the Blessed William. Kidd became captain, either the result of an election of the ship's crew or because of appointment by Christopher Codrington, governor of the island of Nevis. Captain Kidd and the Blessed William became part of a small fleet assembled by Codrington to defend Nevis from the French, with whom the English were at war. In either case, he must have been an experienced leader and sailor by that time. As the governor did not want to pay the sailors for their defensive services, he told them they could take their pay from the French. Kidd and his men attacked the French island of Mariegalante, destroyed the only town, and looted the area, gathering for themselves something around 2,000 pounds Sterling. During the War of the Grand Alliance, on orders from the province of New York, Massachusetts, Kidd captured an enemy privateer, which duty he was commissioned to perform off the New England coast. Shortly thereafter, Kidd was awarded 150 lires for successful privateering in the Caribbean. One year later, Captain Robert Culliford, a notorious pirate, stole Kidd's ship while he was ashore at Antigua in the West Indies. In 1695, William III of England replaced the corrupt governor Benjamin Fletcher, known for accepting bribes of one hundred dollars to allow illegal trading of pirate loot, with Richard Coote, Earl of Bellomont. In New York City, Kidd was active in the building of Trinity Church, New York.

On 16 May 1691, Kidd married Sarah Bradley Cox Oort, an English woman in her early twenties, who had already been twice widowed and was one of the wealthiest women in New York, largely because of her inheritance from her first husband.

On 11 December 1695, Belmont, who was now governing New York, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, asked the "trusty and well beloved Captain Kidd" to attack Thomas Tew, John Ireland, Thomas Wake, William Maze, and all others who associated themselves with pirates, along with any enemy French ships. This request, if turned down, would have been viewed as disloyalty to the crown, the perception of which carried much social stigma, making it difficult for Kidd to have done so. The request preceded the voyage which established Kidd's reputation as a pirate, and marked his image in history and folklore.

On 11 December 1695, Belmont, who was now governing New York, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, asked the "trusty and well beloved Captain Kidd" to attack Thomas Tew, John Ireland, Thomas Wake, William Maze, and all others who associated themselves with pirates, along with any enemy French ships. This request, if turned down, would have been viewed as disloyalty to the crown, the perception of which carried much social stigma, making it difficult for Kidd to have done so. The request preceded the voyage which established Kidd's reputation as a pirate, and marked his image in history and folklore.In September 1696, Kidd weighed anchor and set course for the Cape of Good Hope. A third of his crew soon perished on the Comoros due to an outbreak of cholera, the brand-new ship developed many leaks, and he failed to find the pirates he expected to encounter off Madagascar. Kidd then sailed to the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb at the southern entrance of the Red Sea, one of the most popular haunts of rovers on the Pirate Round. Here he again failed to find any pirates. According to Edward Barlow, a captain employed by the English East India Company, Kidd attacked a Mughal convoy here under escort by Barlow's East Indiaman, and was repelled. If the report is true, this marked Kidd's first foray into piracy.

Kidd killed one of his own crewmen on 30 October 1697. While Kidd's gunner, William Moore, was on deck sharpening a chisel, a Dutch ship appeared in sight. Moore urged Kidd to attack the Dutchman, an act not only piratical but also certain to anger the Dutch-born King William. Kidd refused, calling Moore a lousy dog. Moore retorted, "If I am a lousy dog, you have made me so; you have brought me to ruin and many more." Kidd snatched up and heaved an ironbound bucket at Moore. Moore fell to the deck with a fractured skull and died the following day.

Acts of savagery on Kidd's part were reported by escaped prisoners, who told stories of being hoisted up by the arms and drubbed with a drawn cutlass. On one occasion, crew members ransacked the trading ship Mary and tortured several of its crew members while Kidd and the other captain, Thomas Parker, conversed privately in Kidd's cabin. When Kidd found out what had happened, he was outraged and forced his men to return most of the stolen property.

Kidd was declared a pirate very early in his voyage by a Royal Navy officer to whom he had promised "thirty men or so". Kidd sailed away during the night to preserve his crew, rather than subject them to Royal Navy.

On 30 January 1698, he raised French colours and took his greatest prize, an Armenian ship, the 400 ton Quedagh Merchant, which was loaded with satins, muslins, gold, silver, an incredible variety of East Indian merchandise, as well as extremely valuable silks. The captain of the Quedagh Merchant was an Englishman named Wright, who had purchased passes from the French East India Company promising him the protection of the French Crown. After realising the captain of the taken vessel was an Englishman, Kidd tried to persuade his crew to return the ship to its owners, but they refused, claiming that their prey was perfectly legal as Kidd was commissioned to take French ships, and that an Armenian ship counted as French if it had French passes. In an attempt to maintain his tenuous control over his crew, Kidd relented and kept the prize. When this news reached England, it confirmed Kidd's reputation as a pirate, and various naval commanders were ordered to "pursue and seize the said Kidd and his accomplices" for the "notorious piracies" they had committed.

On 30 January 1698, he raised French colours and took his greatest prize, an Armenian ship, the 400 ton Quedagh Merchant, which was loaded with satins, muslins, gold, silver, an incredible variety of East Indian merchandise, as well as extremely valuable silks. The captain of the Quedagh Merchant was an Englishman named Wright, who had purchased passes from the French East India Company promising him the protection of the French Crown. After realising the captain of the taken vessel was an Englishman, Kidd tried to persuade his crew to return the ship to its owners, but they refused, claiming that their prey was perfectly legal as Kidd was commissioned to take French ships, and that an Armenian ship counted as French if it had French passes. In an attempt to maintain his tenuous control over his crew, Kidd relented and kept the prize. When this news reached England, it confirmed Kidd's reputation as a pirate, and various naval commanders were ordered to "pursue and seize the said Kidd and his accomplices" for the "notorious piracies" they had committed.On 1 April 1698, Kidd reached Madagascar. Here he found the first pirate of his voyage, Robert Culliford (the same man who had stolen Kidd’s ship years before), and his crew aboard the Mocha Frigate. Two contradictory accounts exist of how Kidd reacted to his encounter with Culliford. According to The General History of the Pirates, published more than 25 years after the event by an author whose very identity remains in dispute, Kidd made peaceful overtures to Culliford: he "drank their Captain's health," swearing that "he was in every respect their Brother," and gave Culliford "a Present of an Anchor and some Guns." This account appears to be based on the testimony of Kidd's crewmen Joseph Palmer and Robert Bradinham at his trial. The other version was presented by Richard Zacks in his 2002 book The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd. According to Zacks, Kidd was unaware that Culliford had only about 20 crew with him, and felt ill manned and ill equipped to take the Mocha Frigate until his two prize ships and crews arrived, so he decided not to molest Culliford until these reinforcements came. After the Adventure Prize and Rouparelle came in, Kidd ordered his crew to attack Culliford's Mocha Frigate. However, his crew, despite their previous eagerness to seize any available prize, refused to attack Culliford and threatened instead to shoot Kidd. Zacks does not refer to any source for his version of events.

Both accounts agree that most of Kidd's men now abandoned him for Culliford. Only 13 remained with the Adventure Galley. Deciding to return home, Kidd left the Adventure Galley behind, ordering her to be burnt because she had become worm-eaten and leaky. Before burning the ship, he was able to salvage every last scrap of metal, such as hinges. With the loyal remnant of his crew, he returned to the Caribbean aboard the Adventure Prize.

Prior to Kidd returning to New York City, he learned that he was a wanted pirate, and that several English men-of-war were searching for him. Realizing that the Adventure Prize was a marked vessel, he cached it in the Caribbean Sea and continued toward New York aboard a sloop. He deposited some of his treasure on Gardiners Island, hoping to use his knowledge of its location as a bargaining tool.

Bellomont (an investor) was away in Boston, Massachusetts. Aware of the accusations against Kidd, Bellomont was justifiably afraid of being implicated in piracy himself, and knew that presenting Kidd to England in chains was his best chance to save himself. He lured Kidd into Boston with false promises of clemency, then ordered him arrested on 6 July 1699. Kidd was placed in Stone Prison, spending most of the time in solitary confinement. His wife, Sarah, was also imprisoned. The conditions of Kidd's imprisonment were extremely harsh, and appear to have driven him at least temporarily insane.

He was eventually (after over a year) sent to England for questioning by Parliament. The new Tory ministry hoped to use Kidd as a tool to discredit the Whigs who had backed him, but Kidd refused to name names, naively confident his patrons would reward his loyalty by interceding on his behalf. There is speculation that he probably would have been spared had he talked. Finding Kidd politically useless, the Tory leaders sent him to stand trial before the High Court of Admiralty in London for the charges of piracy on high seas and the murder of William Moore. Whilst awaiting trial, Kidd was confined in the infamous Newgate Prison and wrote several letters to King William requesting clemency.

Kidd had two lawyers to assist in his defence. He was shocked to learn at his trial that he was charged with murder. He was found guilty on all charges (murder and five counts of piracy). He was hanged on 23 May 1701, at 'Execution Dock', Wapping, in London. During the execution, the hangman's rope broke and Kidd was hanged on the second attempt. His body was gibbeted over the River Thames at Tilbury Point - as a warning to future would-be pirates - for three years.

His associates Richard Barleycorn, Robert Lamley, William Jenkins, Gabriel Loffe, Able Owens, and Hugh Parrot were convicted, but pardoned just prior to hanging at Execution Dock.

Kidd's Whig backers were embarrassed by his trial. Far from rewarding his loyalty, they participated in the effort to convict him by depriving him of the money and information which might have provided him with some legal defence. In particular, the two sets of French passes he had kept were missing at his trial. These passes (and others dated 1700) resurfaced in the early twentieth century, misfiled with other government papers in a London building. These passes call the extent of Kidd's guilt into question. Along with the papers, many goods were brought from the ships and soon auctioned off as "pirate plunder." They were never mentioned in the trial. Nevertheless, none of these items would have prevented his conviction for murdering Moore.

Kidd's Whig backers were embarrassed by his trial. Far from rewarding his loyalty, they participated in the effort to convict him by depriving him of the money and information which might have provided him with some legal defence. In particular, the two sets of French passes he had kept were missing at his trial. These passes (and others dated 1700) resurfaced in the early twentieth century, misfiled with other government papers in a London building. These passes call the extent of Kidd's guilt into question. Along with the papers, many goods were brought from the ships and soon auctioned off as "pirate plunder." They were never mentioned in the trial. Nevertheless, none of these items would have prevented his conviction for murdering Moore.As to the accusations of murdering Moore, on this he was mostly sunk on the testimony of the two former crew members, Palmer and Bradinham, who testified against him in exchange for pardons. A deposition Palmer gave when he was captured in Rhode Island two years earlier contradicted his testimony and may have supported Kidd's assertions, but Kidd was unable to obtain the deposition.

A broadside song Captain Kidd's Farewell to the Seas, or, the Famous Pirate's Lament was printed shortly after his execution and popularised the common belief that Kidd had confessed to the false charges.

Sources: Wikipedia

This work released through CC 3.0 By-SA - Creative Commons

Monday, March 24, 2014

Baby Face Nelson: American Gangster

Lester Joseph Gillis (December 6, 1908 – November 27, 1934), known under the pseudonym George Nelson, was a bank robber and murderer in the 1930s. Gillis was better known as Baby Face Nelson, a name given to him due to his youthful appearance and small stature. Usually referred to by criminal associates as "Jimmy". Nelson entered into a partnership with John Dillinger, helping him escape from prison in the famed Crown Point, Indiana Jail escape, and was later labeled along with the remaining gang members as public enemy number one.

Lester Joseph Gillis (December 6, 1908 – November 27, 1934), known under the pseudonym George Nelson, was a bank robber and murderer in the 1930s. Gillis was better known as Baby Face Nelson, a name given to him due to his youthful appearance and small stature. Usually referred to by criminal associates as "Jimmy". Nelson entered into a partnership with John Dillinger, helping him escape from prison in the famed Crown Point, Indiana Jail escape, and was later labeled along with the remaining gang members as public enemy number one.Nelson was responsible for the murder of several people, and has the dubious distinction of having killed more FBI agents in the line of duty than any other person. Nelson was shot by FBI agents and died after a shootout often termed "The Battle of Barrington".

On July 4, 1921, at the age of twelve, Nelson was arrested after accidentally shooting a fellow child in the jaw with a pistol he had found. He served over a year in the state reformatory. Arrested again for theft and joyriding at age 13, he was sent to a penal school for an additional 18 months.

By 1928, Nelson was working at a Standard Oil station in his neighborhood that was the headquarters of young tire thieves, known as "strippers". After falling in with them, Nelson became acquainted with many local criminals, including one who gave him a job driving bootleg alcohol throughout the Chicago suburbs. It was through this job that Nelson became associated with members of the suburban-based Touhy Gang (not the Capone mob, as usually reported). Within two years, Nelson and his gang had graduated to armed robbery. On January 6, 1930, they invaded the home of magazine executive Charles M. Richter. After trussing him up with adhesive tape and cutting the phone lines, they ransacked the house and made off with $25,000 worth of jewelry. Two months later, they carried out a similar theft in the Sheridan Road bungalow of Lottie Brenner Von Buelow. This job netted $50,000 in jewels, including the wedding ring of the bank's owner. Chicago newspapers nicknamed them "The Tape Bandits."

On April 21, 1933, Nelson robbed his first bank, making off with $4,000. A month later, Nelson and his gang pulled their home invasion scheme again, netting $25,000 worth of jewels. On October 3 of that year, Nelson hit the Itasca State Bank for $4,600; a teller later identified Nelson as one of the robbers. Three nights later, Nelson stole the jewelry of the wife of Chicago mayor Big Bill Thompson, valued at $18,000. She later described her attacker this way, "He had a baby face. He was good looking, hardly more than a boy, had dark hair and was wearing a gray topcoat and a brown felt hat, turned down brim." Years later, Nelson and his crew were linked to a botched roadhouse robbery in Summit, Illinois on November 23, 1930 that resulted in gunplay that left three people dead and three others wounded. Three nights later, the Tape Bandits hit a Waukegan Road tavern, and Nelson ended up committing his first murder of note, when he killed stockbroker Edwin R. Thompson.

Throughout the winter of 1931, most of the Tape Bandits were rounded up, including Nelson. The Chicago Tribune referred to their leader as "George 'Baby Face' Nelson" who received a sentence of one year to life in the state penitentiary at Joliet. In February 1932, Nelson escaped during a prison transfer. Through his contacts in the Touhy Gang, Nelson fled west and took shelter with Reno gambler/crime boss William Graham. Using the alias of "Jimmy Johnson", Nelson wound up in Sausalito California, working for bootlegger Joe Parente. During these San Francisco Bay area criminal ventures, Nelson most probably first met John Paul Chase and Fatso Negri, two men who were at his side during the later half of his career. While in Reno the next winter, Nelson first met the vacationing Alvin Karpis, who in turn introduced him to Midwestern bank robber Eddie Bentz. Teaming with Bentz, Nelson returned to the Midwest the next summer and committed his first major bank robbery in Grand Haven, Michigan on August 18, 1933. The robbery was a near-disaster, even though most of those involved made a clean getaway.

Throughout the winter of 1931, most of the Tape Bandits were rounded up, including Nelson. The Chicago Tribune referred to their leader as "George 'Baby Face' Nelson" who received a sentence of one year to life in the state penitentiary at Joliet. In February 1932, Nelson escaped during a prison transfer. Through his contacts in the Touhy Gang, Nelson fled west and took shelter with Reno gambler/crime boss William Graham. Using the alias of "Jimmy Johnson", Nelson wound up in Sausalito California, working for bootlegger Joe Parente. During these San Francisco Bay area criminal ventures, Nelson most probably first met John Paul Chase and Fatso Negri, two men who were at his side during the later half of his career. While in Reno the next winter, Nelson first met the vacationing Alvin Karpis, who in turn introduced him to Midwestern bank robber Eddie Bentz. Teaming with Bentz, Nelson returned to the Midwest the next summer and committed his first major bank robbery in Grand Haven, Michigan on August 18, 1933. The robbery was a near-disaster, even though most of those involved made a clean getaway.

The Grand Haven bank job apparently convinced Nelson he was ready to lead his own gang. Through connections in St. Paul's Green Lantern Tavern, Nelson recruited Homer Van Meter, Tommy Carroll, and Eddie Green. With these men (and two other local thieves), Nelson robbed the First National Bank of Brainerd, Minnesota of $32,000 on October 23, 1933. Witnesses reported that Nelson wildly sprayed sub-machine gun bullets at bystanders as he made his getaway. After collecting his wife Helen and four-year old son Ronald, Nelson left with his crew for San Antonio, Texas. While here, Nelson and his gang bought several weapons from underworld gunsmith Hyman Lehman. One of those weapons was a .38 Colt automatic pistol that had been modified to fire fully automatic (Nelson used this same gun to murder Special Agent W. Carter Baum at Little Bohemia Lodge several months later).

By December 9, a local woman tipped San Antonio police to the nearby presence of "high powered Northern gangsters". Two days later, Tommy Carroll was cornered by two detectives and opened fire, killing Detective H.C. Perrin and wounding Detective Al Hartman. All the Nelson gang, except for Nelson, fled San Antonio. Nelson and his wife traveled west to the San Francisco Bay Area, where he recruited John Paul Chase and Fatso Negri for a new wave of bank robberies in the coming spring.

By December 9, a local woman tipped San Antonio police to the nearby presence of "high powered Northern gangsters". Two days later, Tommy Carroll was cornered by two detectives and opened fire, killing Detective H.C. Perrin and wounding Detective Al Hartman. All the Nelson gang, except for Nelson, fled San Antonio. Nelson and his wife traveled west to the San Francisco Bay Area, where he recruited John Paul Chase and Fatso Negri for a new wave of bank robberies in the coming spring.On March 3, 1934, John Dillinger made his famous "wooden pistol" escape from the jail in Crown Point, Indiana. Although the details remain in some dispute, the escape is suspected to have been arranged and financed by members of Nelson's newly formed gang, including Homer Van Meter, Tommy Carroll, Eddie Green, and John "Red" Hamilton, with the understanding that Dillinger would repay some part of the bribe money out of his share of the first robbery. The night Dillinger arrived in the Twin Cities, Nelson and his friend John Paul Chase were driving when they were cut off by a car driven by a local paint salesman named Theodore Kidder. Nelson lost his temper and gave chase, crowding Kidder to the curb. When the salesman got out to protest, Nelson fatally shot him.

Two days after this, the new gang (with Hamilton's participation as the sixth man uncertain) struck the Security National Bank at Sioux Falls, South Dakota. In the robbery, which netted around $49,000 (figures differ slightly), Nelson severely wounded motorcycle policeman Hale Keith with a burst of sub-machine-gun fire as the officer was arriving at the scene.

The six men would soon be identified as "the second Dillinger gang", due to Dillinger's extreme notoriety, but the gang had no leader. On March 13, the gang struck again at the First National Bank in Mason City, Iowa. Dillinger and Hamilton both were shot and wounded in the robbery, where they made away with $52,000. On April 3, federal agents ambushed and killed Eddie Green, though he was unarmed and they were uncertain of his identity. In the aftermath of the Mason City robbery, Nelson and John Paul Chase fled west to Reno, where their old bosses Bill Graham and Jim McKay were fighting a federal mail fraud case. Years later, the FBI determined that, on March 22, 1934, Nelson and Chase abducted the chief witness against the pair, Roy Fritsch, and killed him. Fritsch's quartered body, while never found, was said to have been thrown down an abandoned mine shaft.

The six men would soon be identified as "the second Dillinger gang", due to Dillinger's extreme notoriety, but the gang had no leader. On March 13, the gang struck again at the First National Bank in Mason City, Iowa. Dillinger and Hamilton both were shot and wounded in the robbery, where they made away with $52,000. On April 3, federal agents ambushed and killed Eddie Green, though he was unarmed and they were uncertain of his identity. In the aftermath of the Mason City robbery, Nelson and John Paul Chase fled west to Reno, where their old bosses Bill Graham and Jim McKay were fighting a federal mail fraud case. Years later, the FBI determined that, on March 22, 1934, Nelson and Chase abducted the chief witness against the pair, Roy Fritsch, and killed him. Fritsch's quartered body, while never found, was said to have been thrown down an abandoned mine shaft.On the afternoon of April 20, Nelson, Dillinger, Van Meter, Carroll, Hamilton, and gang associate (errand-runner) Pat Reilly, accompanied by Nelson's wife Helen and three girlfriends of the other men, arrived at the secluded Little Bohemia Lodge in Manitowish Waters, Wisconsin, for a weekend of rest. The gang's connection to the resort apparently came from the past dealings between Dillinger's attorney, Louis Piquett, and lodge owner Emil Wanatka. Though gang members greeted him by name, Wanatka maintained that he was unaware of their identities until some time on Friday night. According to Bryan Burrough's book Public Enemies: America's Greatest Crime Wave and the Birth of the FBI, 1933–34, this most likely happened when Wanatka was playing cards with Dillinger, Nelson, and Hamilton. When Dillinger won a round and raked in the pot, Wanatka caught a glimpse of Dillinger's pistol concealed in his coat, and noticed that Nelson and the others also had shoulder holsters.

The following day, while she was away from the lodge with her young son at a children's birthday party, Wanatka's wife informed a friend, Henry Voss, that the Dillinger gang was at the lodge, and the F.B.I. was subsequently given the tip early on April 22. Melvin Purvis and a number of agents arrived by plane from Chicago, and with the gang's departure imminent, attacked the lodge quickly and with little preparation, and without notifying or obtaining help from local authorities.

Wanatka offered a one-dollar dinner special on Sunday nights, and the last of a crowd estimated at 75 were leaving as the agents arrived in the front driveway. A 1933 Chevrolet coupé was leaving at that moment with three departing lodge customers, John Hoffman, Eugene Boisneau and John Morris, who apparently did not hear an order to halt because the car radio drowned out the agents yelling at them to stop. The agents quickly opened fire on them, instantly killing Boisneau and wounding the others, and alerting the gang members inside.

Adding to the chaos, at this moment Pat Reilly returned to the lodge after an out-of-town errand for Van Meter, accompanied by one of the gang's girlfriends, Pat Cherrington. Accosted by the agents, Reilly and Cherrington backed out and escaped under fire, after a number of misfortunes.

Dillinger, Van Meter, Hamilton, and Carroll immediately escaped through the back of the lodge, which was unguarded, and made their way north on foot through woods and past a lake to commandeer a car and a driver at a resort a mile away. Carroll was not far behind them. He made it to Manitowish and stole a car, making it uneventfully to St. Paul.

Nelson, who had been outside the lodge in the adjacent cabin (he supposedly was irked that Dillinger got a better room), characteristically attacked the raiding party head on, exchanging fire with Purvis, before retreating into the lodge under a return volley from other agents. From there he slipped out the back and fled in the opposite direction from the others. Emerging from the woods ninety minutes later, a mile away from Little Bohemia, Nelson kidnapped the Lange couple from their home and ordered them to drive him away. Apparently dissatisfied with the car's speed, he quickly ordered them to pull up at a brightly lit house where the switchboard operator, Alvin Koerner, aware of the ongoing events, quickly phoned authorities at one of the involved lodges to report a suspicious vehicle in front of his home. Shortly after Nelson had entered the home, taking the Koerners hostage, Emil Wanatka arrived with his brother-in-law George LaPorte and a lodge employee (while a fourth man remained in the car) and were also taken prisoner. Nelson ordered Koerner and Wanatka back into their vehicle, where the fourth man remained unnoticed in the back seat.

As they were preparing to leave, with Wanatka driving at gunpoint, another car arrived with two federal agents – W. Carter Baum and Jay Newman, and a local constable, Carl Christensen. Nelson quickly took them by surprise at gunpoint and ordered them out of their car. As Newman, the driver was getting out, Nelson, apparently detecting a suspicious movement, opened fire with a custom-converted machine gun pistol, severely wounding Christensen and Newman and killing Baum, shot three times in the neck. Nelson was later quoted as having said that Baum had him "cold" and couldn't understand why he hadn't fired. It was found that the safety catch on Baum's gun was on.

Nelson then stole the FBI car. Less than 15 miles away, the car suffered a flat tire and finally became mired in mud as Nelson attempted unsuccessfully to change it. Back on foot, he wandered into the woods and took up residence with a Chippewa family in their secluded cabin for several days before making his final escape in another commandeered vehicle.

Three of the women who had accompanied the gang, including Nelson's wife Helen Gillis, were captured inside the lodge. After grueling interrogation by the F.B.I., the three were ultimately convicted on harboring charges and released on parole.

With an agent and an innocent bystander dead, and four more severely wounded, including two more innocent bystanders, and the complete escape of the Dillinger gang, the F.B.I came under severe criticism, with calls for J. Edgar Hoover's resignation and a widely circulated petition demanding Purvis' suspension.

At the time of the Little Bohemia shootout, Nelson's identity as a member of the Dillinger gang had been known to the F.B.I. for only two weeks. Following the killing of Baum, Nelson became nationally notorious and was made a high-priority target of the Bureau. The focus on him and the murdered agent also served to deflect some of the intense criticism directed at Hoover and Purvis following the Little Bohemia debacle.

At the time of the Little Bohemia shootout, Nelson's identity as a member of the Dillinger gang had been known to the F.B.I. for only two weeks. Following the killing of Baum, Nelson became nationally notorious and was made a high-priority target of the Bureau. The focus on him and the murdered agent also served to deflect some of the intense criticism directed at Hoover and Purvis following the Little Bohemia debacle.A day after the Little Bohemia raid, Dillinger, Hamilton, and Van Meter ran through a police road block near Hastings, Minnesota, drawing fire from officers there. A ricocheting bullet struck Hamilton in the back, fatally wounding him. Hamilton reportedly died in hiding on April 30 or May 1, 1934, and was secretly buried by Dillinger and others including Nelson, who had rejoined the gang in Aurora, Illinois.

On June 7, gang member Tommy Carroll was killed when trying to escape arrest in Waterloo, Iowa. Carroll and his girlfriend Jean Crompton (who had been captured and tried with Helen Gillis after Little Bohemia) had grown close to the Nelsons, and his death was a personal blow to them. The couple went into hiding during the ensuing weeks, and although they were in the Chicago area, their precise movements in this period remain obscure. The Nelsons reportedly lived in various tourist camps, while continuing to secretly meet with family members whenever possible.

On June 27, former gang errand-runner and Little Bohemia fugitive Pat Reilly was surrounded as he slept and was captured alive in St. Paul, Minnesota.

On the morning of June 30, Nelson, Dillinger, Van Meter, and one or more additional accomplices robbed the Merchants National Bank in South Bend, Indiana. One man involved in the robbery is believed to have possibly been Pretty Boy Floyd, based on several eyewitness identifications as well as the later account of Joseph "Fatso" Negri, an old Nelson associate from California who was serving as a gofer to the gang at this time. Another rumored participant was Nelson's childhood friend Jack Perkins, also an associate of the gang at that time. (Perkins would later be tried for the robbery and acquitted).

When the robbery began, a policeman named Howard Wagner had been directing traffic outside; responding quickly to the scene and attempting to draw his gun, he was shot dead by Van Meter, who was stationed outside the bank. Also outside the bank, Nelson exchanged fire with a local jeweler, Harry Berg, who had shot him in the chest - ineffectively, because of Nelson's bullet-proof vest. As Berg retreated into his store under a return volley from Nelson, a man in a parked car was wounded. Nelson also grappled briefly with a teenage boy, Joseph Pawlowski, who tackled him until Nelson (or Van Meter) stunned Powlowski with a blow from his gun. When Dillinger and the man identified as Floyd (unconfirmed) emerged from the bank with sacks containing $28,000, they brought three hostages with them (including the bank president) to deter gunfire from three patrolmen on the scene. The policemen fired nonetheless, wounding two of the hostages before grazing Van Meter in the head. The gang escaped, and Van Meter recovered. In the constant and chaotic exchange of gunfire, several other bystanders were wounded by shots, ricochets, or flying broken glass. It proved to be the last confirmed robbery for all of the known and suspected participants, including Floyd (unconfirmed).

During the month of July, as the FBI manhunt for him continued, Nelson and his wife fled to California with associate John Paul Chase, who would remain with Nelson for the rest of his life. Upon their return to Chicago on July 15, the gang held a reunion meeting at a favorite rendezvous site. When the meeting was interrupted by two Illinois state troopers, Fred McAllister and Gilbert Cross, Nelson fired on their vehicle with his converted "machine gun pistol", wounding both men as the gangsters retreated. Cross was badly injured, but both men survived. Nelson's responsibility was uncertain until verification came later in the form of a confession from Chase.

On July 22, 1934, Dillinger was ambushed and killed by FBI agents outside the Biograph Theater in Lincoln Park, Chicago. The next day the FBI announced that "Pretty Boy" Floyd was now Public Enemy No. 1. On October 22, 1934, Floyd was killed in a shootout with agents including Melvin Purvis. Subsequently, J. Edgar Hoover announced that "Baby Face" Nelson was now Public Enemy No. 1.

On August 23, Van Meter was ambushed and killed by police in St. Paul, Minnesota, leaving Nelson as the sole survivor of the so-called "Second Dillinger Gang".

In the ensuing months, Nelson and his wife, usually accompanied by Chase, drifted west to cities including Sacramento and San Francisco, California and Reno and Las Vegas, Nevada. They often stayed in auto camps, including Walley's Hot Springs, outside of Genoa, Nevada, where they hid out from October 1 before returning to Chicago around November 1. Nelson's movements during the final month of his life are largely unknown.

By the end of the month, FBI interest had settled on a former hideout of Nelson's, the Lake Como Inn in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, where it was believed that Nelson might return for the winter. When the Nelsons and Chase did return to the inn on November 27, they briefly came face to face with surprised and unprepared FBI agents who had staked it out. The fugitives sped away before any shots were fired. Armed with a description of the car (a black Ford V8) and its license plate number (639-578), agents swarmed into the area.

A short but furious gun battle between FBI agents and Nelson took place on November 27, 1934 outside Chicago in the town of Barrington, resulting in the deaths of Nelson and FBI Special Agents Herman "Ed" Hollis and Samuel P. Cowley.

A short but furious gun battle between FBI agents and Nelson took place on November 27, 1934 outside Chicago in the town of Barrington, resulting in the deaths of Nelson and FBI Special Agents Herman "Ed" Hollis and Samuel P. Cowley.The Barrington gun battle erupted as Nelson, with Helen Gillis and John Paul Chase as passengers, drove a stolen V8 Ford south towards Chicago on State Highway 14. Nelson, always keen to spot G-Men, caught sight of a sedan driven in the opposite direction by FBI agents Thomas McDade and William Ryan. Nelson hated police and federal agents and used a list of license plates he had compiled to hunt them at every opportunity. The agents and the outlaw simultaneously recognized each other and after several U-turns by both vehicles, Nelson wound up in pursuit of the agents' car. Nelson and Chase fired at the agents and shattered their car's windshield. After swerving to avoid an oncoming milk truck, Ryan and McDade skidded into a field and anxiously awaited Nelson and Chase who had stopped pursuing. The agents did not know that a shot fired by Ryan had punctured the radiator of Nelson's Ford or that the Ford was being pursued by a Hudson automobile driven by two more agents: Herman Hollis (who was alleged to have delivered the fatal shot to a wounded Pretty Boy Floyd a month earlier) and Cowley. As a result, Ryan and McDade were oblivious to the events that happened next.

With his vehicle losing power and his pursuers attempting to pull alongside, Nelson swerved into the entrance of Barrington's North Side Park and stopped opposite three gas stations. Hollis and Cowley overshot them by over 100 feet (30 m), stopped at an angle, exited their vehicle's passenger door, under heavy gun fire from Nelson and Chase and took cover behind the car. The ensuing shootout was witnessed by more than 30 people.

Nelson's wife, fleeing into an open field under instructions from Nelson, turned briefly in time to see Nelson mortally wounded. He grasped his side and sat down on the running board as Chase continued to fire from behind their car. Nelson, advancing toward the agents, fired so rapidly with a .351 rifle that bystanders mistook it for a machine gun. Six bullets from Cowley's submachine gun eventually struck Nelson in the chest and stomach before Nelson mortally wounded Cowley with bullets to the chest and stomach, while pellets from Hollis's shotgun struck Nelson in the legs and knocked him down. As Nelson regained his feet, Hollis, possibly already wounded, moved to better cover behind a utility pole while drawing his pistol but was killed by a bullet to the head before he could return fire. Nelson stood over Hollis's body for a moment, then limped toward the agents's car. Nelson was too badly wounded to drive, so Chase got behind the wheel and the two men and Nelson's wife fled the scene. Nelson had been shot seventeen times; seven of Cowley's bullets had struck his torso and ten of Hollis's shotgun pellets had hit his legs. After telling his wife "I'm done for", Nelson gave directions as Chase drove them to a safe house on Walnut Street in Wilmette. Nelson died in bed with his wife at his side, at 7:35 p.m.

Hollis was severely wounded in the head and was declared dead soon after arriving at the hospital. At a different hospital, Cowley lived for long enough to confer briefly with Melvin Purvis and have surgery, before succumbing to a stomach wound similar to Nelson's. Following an anonymous telephone tip, Nelson's body was discovered wrapped in a blanket by FBI agent Walter Walsh, in front of St. Peter Catholic Cemetery in Skokie, which still exists. Helen Gillis later stated that she had placed the blanket around Nelson's body because, "He always hated being cold..."

Newspapers then reported, based on the questionable wording of an order from J. Edgar Hoover ("...find the woman and give her no quarter"), that the FBI had issued a "death order" for Nelson's widow, who wandered the streets of Chicago as a fugitive for several days, described in print as America's first female "public enemy". After surrendering on Thanksgiving Day, Helen Gillis, who had been paroled after capture at Little Bohemia, served a year in prison for harboring her husband. Chase was apprehended later and served a term at Alcatraz.

Sources: Wikipedia

This work released through CC 3.0 BY-SA - Creative Commons

Friday, March 21, 2014

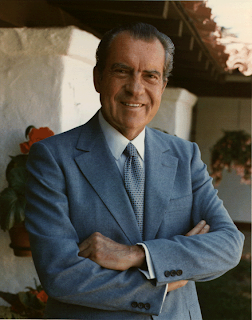

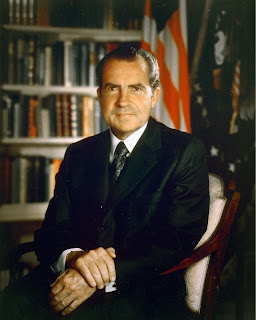

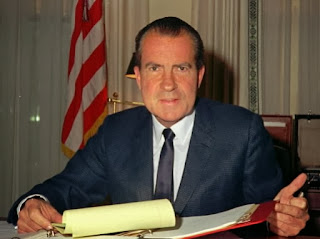

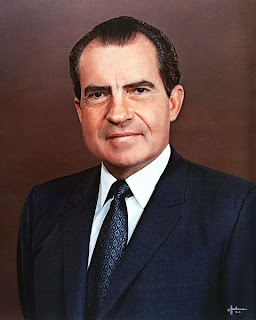

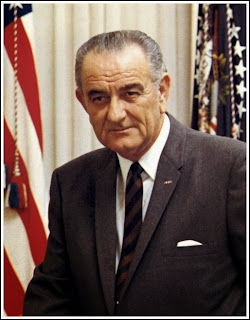

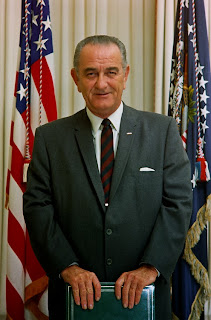

Richard Nixon: The Presidents

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913 – April 22, 1994) was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974, when he became the only president to resign the office. Nixon had previously served as a Republican U.S. Representative and Senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961.

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913 – April 22, 1994) was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974, when he became the only president to resign the office. Nixon had previously served as a Republican U.S. Representative and Senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961.Nixon was born in Yorba Linda, California. He graduated from Whittier College in 1934 and Duke University School of Law in 1937, returning to California to practice law. He and his wife, Pat Nixon, moved to Washington to work for the federal government in 1942. He subsequently served in the United States Navy during World War II. Nixon was elected in California to the House of Representatives in 1946 and to the Senate in 1950. His pursuit of the Alger Hiss case established his reputation as a leading anti-communist, and elevated him to national prominence. He was the running mate of Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Republican Party presidential nominee in the 1952 election. Nixon served for eight years as vice president. He waged an unsuccessful presidential campaign in 1960, narrowly losing to John F. Kennedy, and lost a race for Governor of California in 1962. In 1968, he ran again for the presidency and was elected.

Although Nixon initially escalated America's involvement in the Vietnam War, he subsequently ended U.S. involvement by 1973. Nixon's visit to the People's Republic of China in 1972 opened diplomatic relations between the two nations, and he initiated détente and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty with the Soviet Union the same year. Domestically, his administration generally embraced policies that transferred power from Washington to the states. Among other things, he launched initiatives to fight cancer and illegal drugs, imposed wage and price controls, enforced desegregation of Southern schools, implemented environmental reforms, and introduced legislation to reform healthcare and welfare. Though he presided over the lunar landings beginning with Apollo 11, he replaced manned space exploration with shuttle missions. He was re-elected by a landslide in 1972.

Nixon's second term saw a crisis in the Middle East, resulting in an oil embargo and the restart of the Middle East peace process, as well as a continuing series of revelations about the Watergate scandal. The scandal escalated, costing Nixon much of his political support, and on August 9, 1974, he resigned in the face of almost certain impeachment and removal from office. After his resignation, he accepted a pardon issued by his successor, Gerald Ford. In retirement, Nixon's work as an elder statesman, authoring nine books and undertaking many foreign trips, helped to rehabilitate his public image. He suffered a debilitating stroke on April 18, 1994, and died four days later at the age of 81.

Nixon was born to Francis A. Nixon and Hannah (Milhous) Nixon, on January 9, 1913, in a house his father built, in Yorba Linda, California. His mother was a Quaker (his father converted from Methodism after his marriage), and his upbringing was marked by conservative Quaker observances of the time, such as refraining from alcohol, dancing, and swearing. Nixon had four brothers: Harold (1909–33), Donald (1914–87), Arthur (1918–25), and Edward (born 1930). Four of the five Nixon boys were named after kings who had ruled in historical or legendary England; Richard, for example, was named after Richard the Lionheart. Nixon's father was Scotch-Irish while his mother was German, English, and Irish.

Nixon was born to Francis A. Nixon and Hannah (Milhous) Nixon, on January 9, 1913, in a house his father built, in Yorba Linda, California. His mother was a Quaker (his father converted from Methodism after his marriage), and his upbringing was marked by conservative Quaker observances of the time, such as refraining from alcohol, dancing, and swearing. Nixon had four brothers: Harold (1909–33), Donald (1914–87), Arthur (1918–25), and Edward (born 1930). Four of the five Nixon boys were named after kings who had ruled in historical or legendary England; Richard, for example, was named after Richard the Lionheart. Nixon's father was Scotch-Irish while his mother was German, English, and Irish.Nixon's early life was marked by hardship, and he later quoted a saying of Eisenhower to describe his boyhood: "We were poor, but the glory of it was we didn't know it". The Nixon family ranch failed in 1922, and the family moved to Whittier, California. In an area with many Quakers, Frank Nixon opened a grocery store and gas station. Richard's younger brother Arthur died in 1925 after a short illness. At the age of twelve, Richard was found to have a spot on his lung and, with a family history of tuberculosis, he was forbidden to play sports. Eventually, the spot was found to be scar tissue from an early bout of pneumonia.

Young Richard attended East Whittier Elementary School, where he was president of his eighth-grade class.

His parents believed that attendance at Whittier High School had caused Richard's older brother Harold to live a dissolute lifestyle before the older boy fell ill of tuberculosis (he died of the disease in 1933). Instead, they sent Richard to the larger Fullerton Union High School. He received excellent grades, even though he had to ride a school bus for an hour each way during his freshman year - later, he lived with an aunt in Fullerton during the week. He played junior varsity football, and seldom missed a practice, even though he was rarely used in games. He had greater success as a debater, winning a number of championships and taking his only formal tutelage in public speaking from Fullerton's Head of English, H. Lynn Sheller. Nixon later remembered Sheller's words, "Remember, speaking is conversation ... don't shout at people. Talk to them. Converse with them." Nixon stated that he tried to use the conversational tone as much as possible.

His parents permitted Richard to transfer to Whittier High School for his junior year, beginning in September 1928. At Whittier High, Nixon suffered his first electoral defeat, for student body president. He generally rose at 4 a.m., to drive the family truck into Los Angeles and purchase vegetables at the market. He then drove to the store to wash and display them, before going to school. Harold had been diagnosed with tuberculosis the previous year; when their mother took him to Arizona in the hopes of improving his health, the demands on Richard increased, causing him to give up football. Nevertheless, Richard graduated from Whittier High third in his class of 207 students.

Nixon was offered a tuition grant to attend Harvard University, but Harold's continued illness and the need for their mother to care for him meant Richard was needed at the store. He remained in his hometown and attended Whittier College, his expenses there covered by a bequest from his maternal grandfather. Nixon played for the basketball team; he also tried out for football, but lacked the size to play. He remained on the team as a substitute, and was noted for his enthusiasm. Instead of fraternities and sororities, Whittier had literary societies. Nixon was snubbed by the only one for men, the Franklins; many members of the Franklins were from prominent families but Nixon was not. He responded by helping to found a new society, the Orthogonian Society. In addition to the society, schoolwork, and work at the store, Nixon found time for a large number of extracurricular activities, becoming a champion debater and gaining a reputation as a hard worker. In 1933, he became engaged to Ola Florence Welch, daughter of the Whittier police chief. The two broke up in 1935.

After his graduation from Whittier in 1934, Nixon received a full scholarship to attend Duke University School of Law. The school was new and sought to attract top students by offering scholarships. It paid high salaries to its professors, many of whom had national or international reputations. The number of scholarships was greatly reduced for second- and third-year students, forcing recipients into intense competition. Nixon not only kept his scholarship but was elected president of the Duke Bar Association, inducted into the Order of the Coif, and graduated third in his class in June 1937. He later wrote of his alma mater: "I always remember that whatever I have done in the past or may do in the future, Duke University is responsible in one way or another."

After graduating from Duke, Nixon initially hoped to join the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He received no response to his letter of application and learned years later that he had been hired, but his appointment had been canceled at the last minute due to budget cuts. Instead, he returned to California and was admitted to the bar in 1937. He began practicing with the law firm Wingert and Bewley in Whittier, working on commercial litigation for local petroleum companies and other corporate matters, as well as on wills. In later years, Nixon proudly stated that he was the only modern president to have previously worked as a practicing attorney. Nixon was reluctant to work on divorce cases, disliking frank sexual talk from women. In 1938, he opened up his own branch of Wingert and Bewley in La Habra, California, and became a full partner in the firm the following year.

After graduating from Duke, Nixon initially hoped to join the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He received no response to his letter of application and learned years later that he had been hired, but his appointment had been canceled at the last minute due to budget cuts. Instead, he returned to California and was admitted to the bar in 1937. He began practicing with the law firm Wingert and Bewley in Whittier, working on commercial litigation for local petroleum companies and other corporate matters, as well as on wills. In later years, Nixon proudly stated that he was the only modern president to have previously worked as a practicing attorney. Nixon was reluctant to work on divorce cases, disliking frank sexual talk from women. In 1938, he opened up his own branch of Wingert and Bewley in La Habra, California, and became a full partner in the firm the following year.In January 1938, Nixon was cast in the Whittier Community Players production of The Dark Tower. There he played opposite a high school teacher named Thelma "Pat" Ryan. Nixon described it in his memoirs as "a case of love at first sight" - for Nixon only, as Pat Ryan turned down the young lawyer several times before agreeing to date him. Once they began their courtship, Ryan was reluctant to marry Nixon; they dated for two years before she assented to his proposal. They wed at a small ceremony on June 21, 1940. After a honeymoon in Mexico, the Nixons began their married life in Whittier. They had two children, Tricia (born 1946) and Julie (born 1948).

In January 1942, the couple moved to Washington, D.C., where Nixon took a job at the Office of Price Administration. In his political campaigns, Nixon would suggest that this was his response to Pearl Harbor, but he had sought the position throughout the latter part of 1941. Both Nixon and his wife believed he was limiting his prospects by remaining in Whittier. He was assigned to the tire rationing division, where he was tasked with replying to correspondence. He did not enjoy the role, and four months later, applied to join the United States Navy. As a birthright Quaker, he could have claimed exemption from the draft, and deferments were routinely granted for those in government service. His application was successful, and he was inducted into the Navy in August 1942.

Nixon completed Officers Candidate School and was commissioned as an ensign in October 1942. His first post was as aide to the commander of the Naval Air Station Ottumwa in Iowa. Seeking more excitement, he requested sea duty and was reassigned as the naval passenger control officer for the South Pacific Combat Air Transport Command, supporting the logistics of operations in the South West Pacific theater. He was Officer in Charge of the Combat Air Transport Command at Guadalcanal in the Solomons and later at Green Island (Nissan island) just north of Bougainville. His unit prepared manifests and flight plans for C-47 operations and supervised the loading and unloading of the cargo aircraft. For this service he received a Letter of Commendation for "meritorious and efficient performance of duty as Officer in Charge of the South Pacific Combat Air Transport Command" On October 1, 1943, Nixon was promoted to lieutenant. Nixon earned two service stars and that citation of commendation, although he saw no actual combat. Upon his return to the US, Nixon was appointed the administrative officer of the Alameda Naval Air Station in California. In January 1945, he was transferred to the Bureau of Aeronautics office in Philadelphia to help negotiate the termination of war contracts, and he received another letter of commendation for his work there. Later, Nixon was transferred to other offices to work on contracts and finally to Baltimore. In October 1945, he was promoted to lieutenant commander. He resigned his commission on New Year's Day 1946.

Nixon first gained national attention in 1948 when his investigation, as a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), broke the Alger Hiss spy case. While many doubted Whittaker Chambers' allegations that Hiss, a former State Department official, had been a Soviet spy, Nixon believed them to be true and pressed for the committee to continue its investigation. Under suit for defamation filed by Hiss, Chambers produced documents corroborating his allegations. These included paper and microfilm copies that Chambers turned over to House investigators after having hidden them overnight in a field; they became known as the "Pumpkin Papers". Hiss was convicted of perjury in 1950 for denying under oath he had passed documents to Chambers. In 1948, Nixon successfully cross-filed as a candidate in his district, winning both major party primaries, and was comfortably reelected.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower was nominated for president by the Republicans in 1952. He had no strong preference for a vice presidential candidate, and Republican officeholders and party officials met in a "smoke-filled room" and recommended Nixon to the general, who agreed to the senator's selection. Nixon's youth (he was then 39), stance against communism, and his political base in California - one of the largest states - were all seen as vote-winners by the leaders. Among the candidates considered along with Nixon were Ohio Senator Robert Taft, New Jersey Governor Alfred Driscoll and Illinois Senator Everett Dirksen. On the campaign trail, Eisenhower spoke to his plans for the country, leaving the negative campaigning to his running mate.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower was nominated for president by the Republicans in 1952. He had no strong preference for a vice presidential candidate, and Republican officeholders and party officials met in a "smoke-filled room" and recommended Nixon to the general, who agreed to the senator's selection. Nixon's youth (he was then 39), stance against communism, and his political base in California - one of the largest states - were all seen as vote-winners by the leaders. Among the candidates considered along with Nixon were Ohio Senator Robert Taft, New Jersey Governor Alfred Driscoll and Illinois Senator Everett Dirksen. On the campaign trail, Eisenhower spoke to his plans for the country, leaving the negative campaigning to his running mate.Eisenhower had pledged to give Nixon responsibilities during his term as vice president that would enable him to be effective from the start as a successor. Nixon attended Cabinet and National Security Council meetings and chaired them when Eisenhower was absent. A 1953 tour of the Far East succeeded in increasing local goodwill toward the United States and prompted Nixon to appreciate the potential of the region as an industrial center. He visited Saigon and Hanoi in French Indochina. On his return to the United States at the end of 1953, Nixon increased the amount of time he devoted to foreign relations.

In July 1959, President Eisenhower sent Nixon to the Soviet Union for the opening of the American National Exhibition in Moscow. On July 24, while touring the exhibits with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, the two stopped at a model of an American kitchen and engaged in an impromptu exchange about the merits of capitalism versus communism that became known as the "Kitchen Debate.

In 1960, Nixon launched his first campaign for President of the United States. He faced little opposition in the Republican primaries and chose former Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. as his running mate. His Democratic opponent was John F. Kennedy, and the race remained close for the duration. Nixon campaigned on his experience, but Kennedy called for new blood and claimed the Eisenhower–Nixon administration had allowed the Soviet Union to overtake the U.S. in ballistic missiles (the "missile gap"). A new political medium was introduced in the campaign: televised presidential debates. In the first of four such debates, Nixon appeared pale, with a five o'clock shadow, in contrast to the photogenic Kennedy. Nixon's performance in the debate was perceived to be mediocre in the visual medium of television, though many people listening on the radio thought that Nixon had won. Nixon lost the election narrowly, with Kennedy ahead by only 120,000 votes (0.2 percent) in the popular vote.

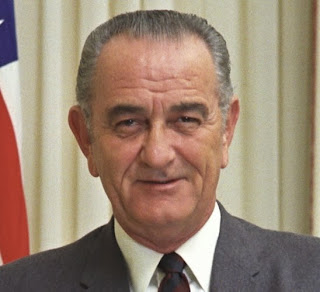

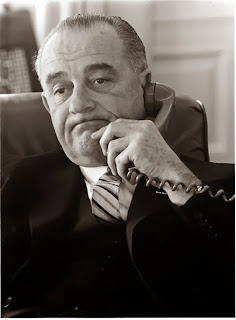

Nixon and Johnson meet at the White House before Nixon's nomination, July 1968.

At the end of 1967, Nixon told his family he planned to run for president a second time. Although Pat Nixon did not always enjoy public life (for example, she had been embarrassed by the need to reveal how little the family owned in the Checkers speech), she was supportive of her husband's ambitions. Nixon believed that with the Democrats torn over the issue of the Vietnam War, a Republican had a good chance of winning, although he expected the election to be as close as in 1960.

Nixon's Democratic opponent in the general election was Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who was nominated at a convention marked by violent protests. Throughout the campaign, Nixon portrayed himself as a figure of stability during a period of national unrest and upheaval. He appealed to what he later called the "silent majority" of socially conservative Americans who disliked the hippie counterculture and the anti-war demonstrators. Agnew became an increasingly vocal critic of these groups, solidifying Nixon's position with the right.

Nixon's Democratic opponent in the general election was Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who was nominated at a convention marked by violent protests. Throughout the campaign, Nixon portrayed himself as a figure of stability during a period of national unrest and upheaval. He appealed to what he later called the "silent majority" of socially conservative Americans who disliked the hippie counterculture and the anti-war demonstrators. Agnew became an increasingly vocal critic of these groups, solidifying Nixon's position with the right.In a three-way race between Nixon, Humphrey, and independent candidate Alabama Governor George Wallace, Nixon defeated Humphrey by nearly 500,000 votes (seven-tenths of a percentage point), with 301 electoral votes to 191 for Humphrey and 46 for Wallace. In his victory speech, Nixon pledged that his administration would try to bring the divided nation together. Nixon said: "I have received a very gracious message from the Vice President, congratulating me for winning the election. I congratulated him for his gallant and courageous fight against great odds. I also told him that I know exactly how he felt. I know how it feels to lose a close one."

Nixon was inaugurated as president on January 20, 1969, sworn in by his onetime political rival, Chief Justice Earl Warren. Pat Nixon held the family Bibles open at Isaiah 2:4, which reads, "They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks." In his inaugural address, which received almost uniformly positive reviews, Nixon remarked that "the greatest honor history can bestow is the title of peacemaker" - a phrase that would later be placed on his gravestone.

When Nixon took office, about 300 American soldiers were dying each week in Vietnam, and the war was broadly unpopular in the United States, with violent protests against the war ongoing. The Johnson administration had agreed to suspend bombing in exchange for negotiations without preconditions, but this agreement never fully took force. According to Walter Isaacson, soon after taking office, Nixon had concluded that the Vietnam War could not be won and he was determined to end the war quickly. Conversely, Black argues that Nixon sincerely believed he could intimidate North Vietnam through the "Madman theory". Nixon sought some arrangement which would permit American forces to withdraw, while leaving South Vietnam secure against attack.

Nixon approved a secret bombing campaign of North Vietnamese and allied Khmer Rouge positions in Cambodia in March 1969 (code-named Operation Menu), a policy begun under Johnson. These operations resulted in heavy bombing of Cambodia; by one measurement more bombs were dropped over Cambodia under Johnson and Nixon than the Allies dropped during World War II. In mid-1969, Nixon began efforts to negotiate peace with the North Vietnamese, sending a personal letter to North Vietnamese leaders, and peace talks began in Paris. Initial talks, however, did not result in an agreement. In July 1969, Nixon visited South Vietnam, where he met with his U.S. military commanders and President Nguyen Van Thieu. Amid protests at home demanding an immediate pullout, he implemented a strategy of replacing American troops with Vietnamese troops, known as "Vietnamization". He soon instituted phased U.S. troop withdrawals but authorized incursions into Laos, in part to interrupt the Ho Chi Minh trail, used to supply North Vietnamese forces, that passed through Laos and Cambodia. Nixon announced the ground invasion of Cambodia to the American public on April 30, 1970. His responses to protesters included an impromptu, early morning meeting with them at the Lincoln Memorial on May 9, 1970. Documents uncovered from the Soviet archives after 1991 reveal that the North Vietnamese attempt to overrun Cambodia in 1970 was launched at the explicit request of the Khmer Rouge and negotiated by Pol Pot's then second in command, Nuon Chea. Nixon's campaign promise to curb the war, contrasted with the escalated bombing, led to claims that Nixon had a "credibility gap" on the issue.

In 1971, excerpts from the "Pentagon Papers", which had been leaked by Daniel Ellsberg, were published by The New York Times and The Washington Post. When news of the leak first appeared, Nixon was inclined to do nothing; the Papers, a history of United States' involvement in Vietnam, mostly concerned the lies of prior administrations and contained few real revelations. He was persuaded by Kissinger that the papers were more harmful than they appeared, and the President tried to prevent publication. The Supreme Court eventually ruled for the newspapers.

As U.S. troop withdrawals continued, conscription was reduced and in 1973 ended; the armed forces became all-volunteer. After years of fighting, the Paris Peace Accords were signed at the beginning of 1973. The agreement implemented a cease fire and allowed for the withdrawal of remaining American troops; however, it did not require the 160,000 North Vietnam Army regulars located in the South to withdraw. Once American combat support ended, there was a brief truce, before fighting broke out again, this time without American combat involvement. North Vietnam conquered South Vietnam in 1975

At the time Nixon took office in 1969, inflation was at 4.7 percent—its highest rate since the Korean War. The Great Society had been enacted under Johnson, which, together with the Vietnam War costs, was causing large budget deficits. There was little unemployment, but interest rates were at their highest in a century. Nixon's major economic goal was to reduce inflation; the most obvious means of doing so was to end the war. This could not be accomplished overnight, and the U.S. economy continued to struggle through 1970, contributing to a lackluster Republican performance in the midterm congressional elections (Democrats controlled both Houses of Congress throughout Nixon's presidency). According to political economist Nigel Bowles in his 2011 study of Nixon's economic record, the new president did little to alter Johnson's policies through the first year of his presidency.

After he won reelection, Nixon found inflation returning. He reimposed price controls in June 1973. The price controls became unpopular with the public and businesspeople, who saw powerful labor unions as preferable to the price board bureaucracy. The controls produced food shortages, as meat disappeared from grocery stores and farmers drowned chickens rather than sell them at a loss. Despite the failure to control inflation, controls were slowly ended, and on April 30, 1974, their statutory authorization lapsed.

After he won reelection, Nixon found inflation returning. He reimposed price controls in June 1973. The price controls became unpopular with the public and businesspeople, who saw powerful labor unions as preferable to the price board bureaucracy. The controls produced food shortages, as meat disappeared from grocery stores and farmers drowned chickens rather than sell them at a loss. Despite the failure to control inflation, controls were slowly ended, and on April 30, 1974, their statutory authorization lapsed.The Nixon years witnessed the first large-scale integration of public schools in the South. Nixon sought a middle way between the segregationist Wallace and liberal Democrats, whose support of integration was alienating some Southern whites. Hopeful of doing well in the South in 1972, he sought to dispose of desegregation as a political issue before then. Soon after his inauguration, he appointed Vice President Agnew to lead a task force, which worked with local leaders - both white and black - to determine how to integrate local schools. Agnew had little interest in the work, and most of it was done by Labor Secretary George Shultz. Federal aid was available, and a meeting with President Nixon was a possible reward for compliant committees. By September 1970, less than ten percent of black children were attending segregated schools. By 1971, however, tensions over desegregation surfaced in Northern cities, with angry protests over the busing of children to schools outside their neighborhood to achieve racial balance. Nixon opposed busing personally but enforced court orders requiring its use.

In addition to desegregating public schools, Nixon implemented the Philadelphia Plan in 1970—the first significant federal affirmative action program. He also endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment after it passed both houses of Congress in 1972 and went to the states for ratification. Nixon had campaigned as an ERA supporter in 1968, though feminists criticized him for doing little to help the ERA or their cause after his election. Nevertheless, he appointed more women to administration positions than Lyndon Johnson had.

After a nearly decade-long national effort, the United States won the race to land astronauts on the Moon on July 20, 1969, with the flight of Apollo 11. Nixon spoke with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin during their moonwalk. He called the conversation "the most historic phone call ever made from the White House". Nixon, however, was unwilling to keep funding for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) at the high level seen through the 1960s as NASA prepared to send men to the Moon. NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine drew up ambitious plans for the establishment of a permanent base on the Moon by the end of the 1970s and the launch of a manned expedition to Mars as early as 1981. Nixon, however, rejected both proposals.

Nixon also canceled the Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory program in 1969, because unmanned spy satellites were shown to be a more cost-effective way to achieve the same reconnaissance objective.

On May 24, 1972, Nixon approved a five-year cooperative program between NASA and the Soviet space program, culminating in the 1975 joint mission of an American Apollo and Soviet Soyuz spacecraft linking in space.

The term Watergate has come to encompass an array of clandestine and often illegal activities undertaken by members of the Nixon administration. Those activities included "dirty tricks" such as bugging the offices of political opponents and people of whom Nixon or his officials were suspicious. Nixon and his close aides ordered harassment of activist groups and political figures, using the FBI, CIA, and the Internal Revenue Service. The activities became known after five men were caught breaking into Democratic party headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. on June 17, 1972. The Washington Post picked up on the story; reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward relied on an informant known as "Deep Throat" - later revealed to be Mark Felt, associate director at the FBI - to link the men to the Nixon administration. Nixon downplayed the scandal as mere politics, calling news articles biased and misleading. A series of revelations made it clear that Nixon aides had committed crimes in attempts to sabotage the Democrats and others, and lied about it. Senior aides such as White House Counsel John Dean and Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman faced prosecution and when it was over 46 others had been convicted.

In July 1973, White House aide Alexander Butterfield testified that Nixon had a secret taping system that recorded his conversations and phone calls in the Oval Office. These tapes were subpoenaed by Watergate Special Counsel Archibald Cox. Nixon refused to release them, citing executive privilege. With the White House and Cox at loggerheads, Nixon had Cox fired in October in the "Saturday Night Massacre"; he was replaced by Leon Jaworski. In November, Nixon's lawyers revealed that an audio tape of conversations, held in the White House on June 20, 1972, featured an 18½ minute gap. Rose Mary Woods, the President's personal secretary, claimed responsibility for the gap, alleging that she had accidentally wiped the section while transcribing the tape, though her tale was widely mocked. The gap, while not conclusive proof of wrongdoing by the President, cast doubt on Nixon's statement that he had been unaware of the cover-up.

In July 1973, White House aide Alexander Butterfield testified that Nixon had a secret taping system that recorded his conversations and phone calls in the Oval Office. These tapes were subpoenaed by Watergate Special Counsel Archibald Cox. Nixon refused to release them, citing executive privilege. With the White House and Cox at loggerheads, Nixon had Cox fired in October in the "Saturday Night Massacre"; he was replaced by Leon Jaworski. In November, Nixon's lawyers revealed that an audio tape of conversations, held in the White House on June 20, 1972, featured an 18½ minute gap. Rose Mary Woods, the President's personal secretary, claimed responsibility for the gap, alleging that she had accidentally wiped the section while transcribing the tape, though her tale was widely mocked. The gap, while not conclusive proof of wrongdoing by the President, cast doubt on Nixon's statement that he had been unaware of the cover-up.Though Nixon lost much popular support, even from his own party, he rejected accusations of wrongdoing and vowed to stay in office. He insisted that he had made mistakes, but had no prior knowledge of the burglary, did not break any laws, and did not learn of the cover-up until early 1973. On October 10, 1973, Vice President Agnew resigned - unrelated to Watergate - and was convicted on charges of bribery, tax evasion and money laundering during his tenure as Governor of Maryland. Nixon chose Gerald Ford, Minority Leader of the House of Representatives, to replace Agnew.

The legal battle over the tapes continued through early 1974, and in April 1974 Nixon announced the release of 1,200 pages of transcripts of White House conversations between him and his aides. The House Judiciary Committee opened impeachment hearings against the President on May 9, 1974, which were televised on the major TV networks. These hearings culminated in votes for impeachment, the first being 27–11 on July 27, 1974 for obstruction of justice. On July 24, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the full tapes, not just selected transcripts, must be released.

Even with support diminished by the continuing series of revelations, Nixon hoped to win. However, one of the new tapes, recorded soon after the break-in, demonstrated that Nixon had been told of the White House connection to the Watergate burglaries soon after they took place, and had approved plans to thwart the investigation. In a statement accompanying the release of the "Smoking Gun Tape" on August 5, 1974, Nixon accepted blame for misleading the country about when he had been told of the truth behind the Watergate break-in, stating that he had a lapse of memory. He met with Republican congressional leaders soon after, and was told he faced certain impeachment in the House and had, at most, only 15 votes in the Senate to vote for his acquittal - far fewer than the 34 he needed to avoid removal from office.

In light of his loss of political support and the near-certainty of impeachment, Nixon resigned the office of the presidency on August 9, 1974, after addressing the nation on television the previous evening. The resignation speech was delivered from the Oval Office and was carried live on radio and television. Nixon stated that he was resigning for the good of the country and asked the nation to support the new president, Gerald Ford. Nixon went on to review the accomplishments of his presidency, especially in foreign policy. He defended his record as president, quoting from Theodore Roosevelt's 1910 speech Citizenship in a Republic:

Nixon's speech contained no admission of wrongdoing, and was termed "a masterpiece" by Conrad Black, one of his biographers. Black opined that "What was intended to be an unprecedented humiliation for any American president, Nixon converted into a virtual parliamentary acknowledgement of almost blameless insufficiency of legislative support to continue. He left while devoting half his address to a recitation of his accomplishments in office." The initial response from network commentators was generally favorable, with only Roger Mudd of CBS stating that Nixon had evaded the issue, and had not admitted his role in the cover-up.